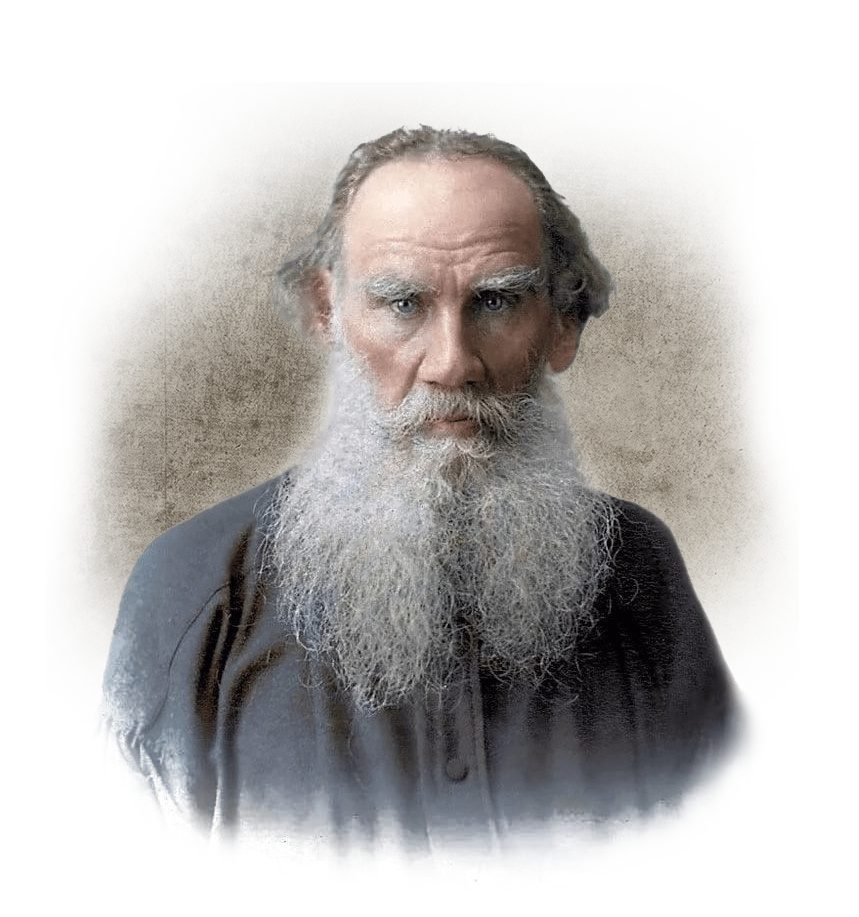

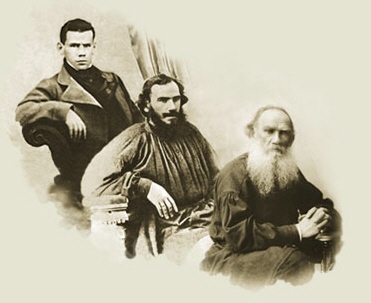

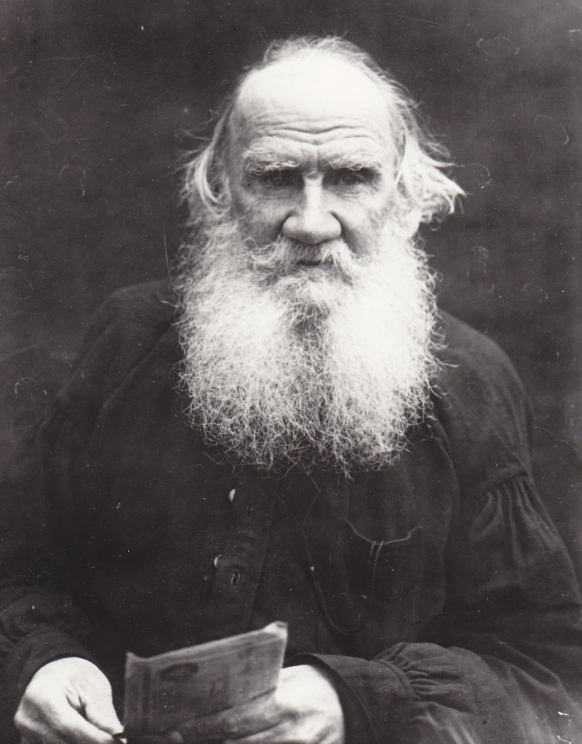

Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy is one of the most famous writers and philosophers in the world. His views and beliefs formed the basis of the whole religious-philosophical movement, which is called Tolstoyism. His literary legacy consists of 90 volumes of fiction and journalism, diary notes and letters, and he was repeatedly nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Nobel Peace Prize.

Leo Nikolayevich wanted to shine in society, but his natural shyness and lack of outward attractiveness hampered him. The various, as Tolstoy himself defines them, «musings» about the most important questions of our existence — happiness, death, God, love, eternity — were imprinted on his character at that time of his life. The story he told in ‘The Youth’ and ‘The Youth’ and in the novel ‘Resurrection’ about the aspirations of Irteniev and Nekhludoff to self-improvement was taken by Tolstoy from the history of his own ascetic attempts of that time. All this, the critic S. A. Vengerov wrote, led to Tolstoy’s «habit of constant moral analysis, which has destroyed the freshness of feeling and the clarity of reason», as he put it in his novel The Youth. In giving examples of self-analysis of this period, he speaks ironically of the exaggeration of his adolescent philosophical ego and grandeur, and at the same time notes the overwhelming inability «to get used to not being ashamed of every simple word and movement» when faced with real people, whose benefactor he then seemed to himself.

Beginning of a literary career

In 1841 Tolstoy’s first eight poem was engraved on a monument to his aunt in Optina hermitage. From March 11, 1847 Tolstoy was in a Kazan hospital, on March 17 he began to keep a diary, where, imitating Benjamin Franklin, he set goals and objectives for self-improvement, noted successes and failures in these tasks, analyzed his shortcomings and thought process, the motives of his actions. He kept this diary at short intervals throughout his life.

Having completed his treatment, in the spring of 1847 Tolstoy abandoned his studies at university and went to his inherited Yasnaya Polyana; his work there is partly described in his Morning of a Landowner: Tolstoy tried to establish a new relationship with the peasants.

In his diary Tolstoy formulated for himself a large number of life rules and goals, but succeeded in following only a small part of them. Among the successful ones are serious studies in English, music, law. In addition, neither his diary nor his letters reflect Tolstoy’s engagement with pedagogy and charity, although in 1849 he first opened a school for peasant children. The principal teacher was Foka Demidovich, a serf, but Leo Tolstoy himself often taught classes.

Participation in the Moscow census

Tolstoy took part in the Moscow census of 1882. He wrote about it as follows: «I proposed to use the census to find out the poverty in Moscow and to help it with deeds and money, and to make sure that there were no poor people in Moscow».

Tolstoy believed that the interest and importance for society of the census is that it gives him a mirror into which all of society and each of us want to look. He chose one of the most difficult areas, Protochny Lane, where there was a night shelter; among Moscow’s rabble this gloomy two-storey building was called ‘Rzhanova Fortress’. Having been instructed by the Duma, Tolstoy began walking around the site a few days before the census on the plan he had been given. Indeed, the filthy dwelling, filled with beggars and desperate people who had sunk to the bottom, served as a mirror for Tolstoy, reflecting the terrible poverty of the people. Freshly impressed by what he saw, Tolstoy wrote his famous article «On the Census in Moscow». In this article, he pointed out that the purpose of the census was scientific, and was a sociological study.

Despite Tolstoy’s declared good aims for the census, the population was suspicious of the undertaking. On this occasion Tolstoy wrote: «When it was explained to us that the people had already learned about the round of flats and were leaving, we asked the landlord to lock the gate, and we ourselves went to the yard to persuade the people to leave». Lev Nikolayevich hoped to arouse sympathy in the rich for urban poverty, raise money, recruit people willing to contribute to the cause, and together with the census go through all the haunts of poverty. In addition to his duties as a census taker, the writer wanted to get in touch with the poor, find out details of their needs and help them with money and work, expulsion from Moscow, placing children in schools, old people and old women in asylums and almshouses.

Philosophy

Tolstoy’s religious and moral imperatives were the source of the Tolstoist movement, built on two fundamental theses: «simplicity» and «non-resistance to evil by violence». The latter, according to Tolstoy, is fixed in a number of places of the Gospel and is the core of Christ’s doctrine, as, indeed, is Buddhism. The essence of Christianity, according to Tolstoy, can be expressed in a simple rule: «Be good and do not counteract evil with violence» — «The law of violence and the law of love» (1908).

The most important basis of Tolstoy’s teachings were the words of the Gospel «Love your enemies» and the Sermon on the Mount. The followers of his teaching, the Tolstoyites, revered the five commandments proclaimed by Leo Tolstoy: Thou shalt not be angry, thou shalt not commit adultery, thou shalt not swear, thou shalt not resist evil by violence, thou shalt love thy enemies as thy neighbor.

Tolstoy developed a particular ideology of non-violent anarchism (it can be described as Christian anarchism), which was based on a rationalistic understanding of Christianity. Considering coercion to be an evil, he concluded that the state should be abolished, but not by means of a revolution based on violence, but by the voluntary refusal of every member of society to perform any state duties, be it military service, payment of taxes, etc. Tolstoy believed: «The anarchists are right in everything, both in denying what exists, and in asserting that under existing mores nothing can be worse than violence of power; but they are grossly mistaken in thinking that anarchy can be established by revolution. Anarchy can only be established by having more and more people who do not need the protection of government power and more and more people who are ashamed to exert that power.»