24.12.2022

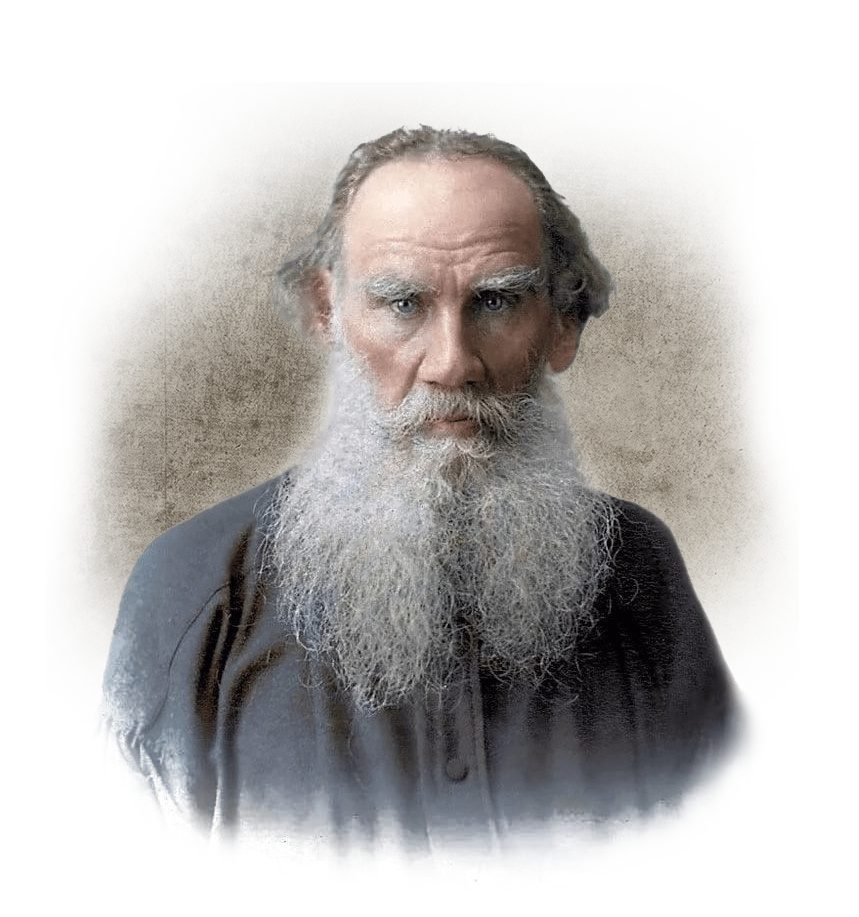

“Resurrection” is the last novel by Leo Tolstoy, written by him in 1889-1899. A social panorama of Russian life in the late 19th century, from the upper to the lower classes: the novel features aristocrats, St Petersburg officials, peasants, convicts, revolutionaries and political prisoners.

Almost immediately after its publication the novel was translated into the main European languages. Such a success was largely due to the acuteness of the chosen theme (the fate of the girl, seduced and abandoned by an officer, whose guilt later becomes a reason to change both their lives) and the tremendous interest in the work of Tolstoy, who had not written a novel since “War and Peace” and “Anna Karenina”.

History of creation

The novel “Resurrection” was written by the author in 1889-1890, 1895-1896, 1898-1899. Three times a year, with interruptions. Initially, the work was written under the title “Konyev’s Tale” because in June 1887 Anatoly Kony told Tolstoy’s story of how one of the jurors during the trial recognized in the prostitute accused of stealing the woman he had once seduced. This woman bore the name Oni and was a prostitute of the lowest grade with a disfigured face. But the seducer, who probably once loved her, decided to marry her and took great pains to do so. His exploit was incomplete: the woman died in prison.

The tragedy of the situation reflects the nature of prostitution and is reminiscent of Guy de Maupassant’s short story “The Port” – a favourite story of Tolstoy, which he translated as “Françoise”: a sailor, arriving from a long voyage, found a brothel in the port, took a woman and recognized her as his sister only when she began to ask him if he had seen this sailor at sea, and told him his own name.

Impressed by all this, Leo Tolstoy asked Kony to give the subject to him. He began to develop the life situation into a conflict, and this work took several years of writing and eleven years of reflection.

While working on the novel, Tolstoy visited Vinogradov, the warden of Butyrsky prison, in January 1899 and questioned him about prison life. In April 1899, Tolstoy came to the Butyrsky prison to travel with the convicts being sent to Siberia as far as the Nikolayevsky railway station and then depicted that way in the novel. When the novel began to be printed, Tolstoy began its revision and literally the night before the publication of the next chapter “will not cease: once started to finish, he could not stop, the more he wrote, the more he was drawn, often remade written, changed, crossed out”.

The complete manuscript collection of the novel exceeds 8000 pages. For comparison, the manuscript of Flaubert’s novel Madame Bovary, which he wrote for 5 years, is 1,788 corrected pages (the final version is 487 pages). Tolstoy had the idea of continuing the novel.

The characters and their prototypes

Katya Maslova

Yekaterina Mikhailovna Maslova is the daughter of an unmarried peasant woman adopted by a passing gypsy. When she is three years old, after her mother dies, the girl is taken in by two old ladies, landlords, and she lives and grows up with them – by Tolstoy’s definition – as “half-maid, half-raised girl”. When she is sixteen, she falls in love with the young Prince Nekhludoff, the landlords’ nephew who has come to visit his aunts. Two years later, on his way to take part in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, Nekhludoff visits his aunts again and, after staying for four days, he seduces the girl, gives her a hundred-ruble note and leaves. Some time later, finding out she is pregnant and no longer expecting Nekhludoff to return, Maslova quarrels with her landlords and asks for the settlement. She gives birth to a child in the house of the village widow-proviductress, the child is taken to the orphanage, where its mother is told it died immediately after her arrival. Having recovered from the birth, Maslova finds a place in the house of a forester, who, waiting for the right moment, rapes her. Soon the forester’s wife catches him with Maslova and starts beating her. Maslova fights back and a brawl ensues, as a result of which she is thrown out without pay.

The woman moves to the city, where, after a series of unsuccessful attempts to find a suitable place for herself, she finds herself in a brothel. In order to assuage her conscience, Maslova has developed a special worldview, in which she is not ashamed of being a prostitute: the main benefit of all men without exception is sexual intercourse with attractive women, and she, an attractive woman, may or may not fulfil this need. In seven years, Maslova has changed two brothels and once ended up in hospital. She ends up in jail on suspicion of being poisoned in order to steal her client’s money, where she will spend six months awaiting trial.

Compared to the fate of Rosalie Oni, Tolstoy’s novel completely reimagines the real story. From the very beginning of the novel, he “approaches” the material, making it more “personal” and the characters more relatable. The scene of Katusha’s seduction is created by Tolstoy already on the basis of his personal memories of his adolescent liaison with the maid Gasha, who lived in his aunt’s house: shortly before his death, Tolstoy told his biographer Biryukov about the “crime” he had committed in his youth by seducing Gasha: “she was innocent, I seduced her, she was driven away, and she died”.

Sophia Tolstaya also wrote about it in her diaries: “I know, he himself has told me at length, that Lev Nikolayevich describes in this scene his liaison with his sister’s maid in Pirogov”.

Dmitry Nekhludoff

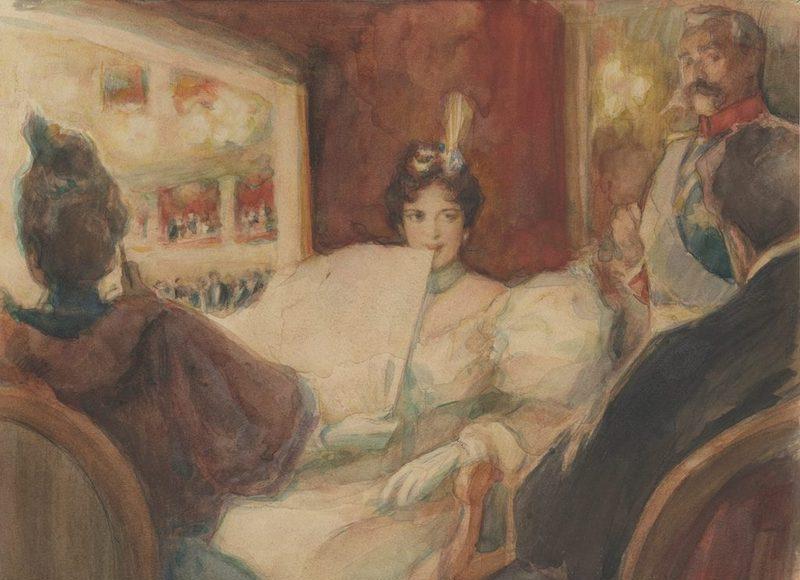

Dmitri Ivanovich Nekhludoff is a prince, a man of high society. The author describes the young Nekhludoff as an honest, self-sacrificing young man, ready to give himself for any good deed and who considers his spiritual being his “real self”. In his youth, Nekhludoff, who dreams of making all people happy, thinks, reads, and speaks of God, truth, wealth, and poverty; considers it necessary to moderate his needs; dreams of a woman only as a wife, and sees the highest spiritual pleasure in sacrifice in the name of moral requirements. This outlook and Nekhludoff’s behaviour are recognised by those around him as strange and boastful originality. When, on reaching adulthood, as an enthusiastic follower of Herbert Spencer and Henry George, and considering land ownership unjust, he gives the peasants the estate he had inherited from his father, this act horrifies his mother and relatives, and becomes a constant object of reproach and derision to all his relatives. At first Nekhludoff tries to fight, but it proves too difficult, and when he cannot stand the struggle, he gives up, becoming what those around him want him to be, completely deadening the voice which demands something else of him. Nekhludoff then enters military service, which, according to Tolstoy’s world view, “corrupts men”. On his way back to the regiment, he visits his aunts in the village, where he seduces Katusha, who is in love with him, and, on the last day before his departure, gives her a hundred-ruble note, comforting himself that “everybody does it”. After leaving the army with the rank of Lieutenant of the Guards, Nekhludoff settles in Moscow, where he leads an idle life of a bored aesthete, a refined egoist who loves only his own pleasure.

In the first unfinished outline of the future novel (then “The Konev Story”), the protagonist’s name is Valerian Yushkov, then – in the same outline – Yushkin. In his attempts to “approximate” the material, Tolstoy initially borrowed for his character the name of his paternal aunt P. I. Yushkova, in whose house he lived in his youth.

It is generally assumed that the image of Nekhludoff is largely autobiographical and reflects Tolstoy’s own change of heart in the eighties, that his wish to marry Maslova is a moment of the theory of “reckoning”. And the initiation of the Gospel at the end of the novel is typical Tolstoyianism.

In the works of Tolstoy, Dmitri Nekhludoff of Resurrection had several literary predecessors. A character with this name first appears in Tolstoy’s story ‘Adolescence’ in 1854. In the story “Youth” he becomes the best friend of Nikolenka Irteniev – the protagonist of the trilogy. Here the young Prince Nekhludoff is one of the brightest characters: clever, educated, tactful. He is a few years older than Nikolenka and acts as his older companion, helping him with advice and keeping him from doing foolish, ill-considered things.

Nekhludoff is also the main character in Tolstoy’s stories ‘Lucerne’ and ‘The Landowner’s Morning’; to these we can also add the story ‘The Cossacks’, in the process of which Tolstoy changed the last name of the central character – Nekhludoff – to Olenin. All these works are largely autobiographical, and in the image of their main characters can easily be guessed Leo Tolstoy himself.

The plot

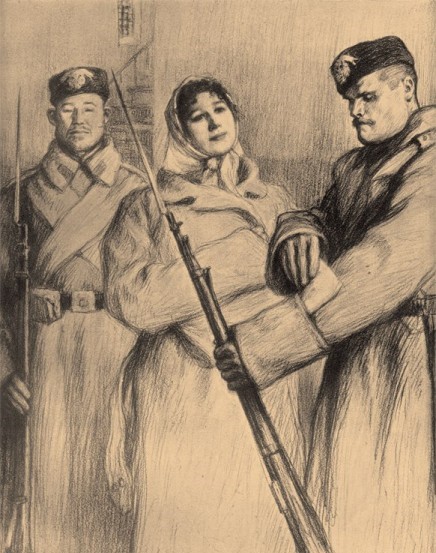

A jury trial is held in the district court on the theft of money and poisoning causing the death of the merchant Smelkoff. Among the three accused is the petty bourgeois Ekaterina Maslova, who is engaged in prostitution. Maslova turns out to be innocent, but as a result of a miscarriage of justice she is sentenced to four years’ hard labour in Siberia.

At the trial, among the jurors, is Prince Dmitry Nekhludoff, who recognises in the defendant Maslova the girl he had seduced and abandoned a decade earlier. Feeling guilty before Maslova, Nekhludoff resolves to hire a prominent solicitor for her, to submit the case for cassation and to lend her money.

Nekhludoff is shocked at the injustice of the trial and at the feelings of loathing and disgust he feels towards all the people he sees that day, especially the high society that surrounds him. He thinks of sooner getting rid of the jury and the society around him and of going abroad. Nekhludoff thinks of Maslova, first as a prisoner, as he had seen her in court, and then, one by one, his memories of the time he had spent with her begin to appear in his mind.

Looking back on his life, Nekhludoff feels like a scoundrel and a scoundrel, and he begins to realise that all the disgust he has felt towards people all that day has essentially been disgust at himself, at the idle and filthy life he has led and, naturally, has found for himself the company of people leading the same life as he does. Wishing by all means to break with this life, Nekhludoff no longer thinks of going abroad – which would be an ordinary escape. He resolves to repent to Katusha, to do everything possible to ease her fate, to ask forgiveness “as the children beg,” and, if necessary, to marry her.

In this state of moral lucidity, of spiritual elation and of the desire to repent, Nekhludoff goes to the prison camp to see Katusha Maslova, but to his astonishment and dismay he finds that the Katusha he had known and loved had long since died; she “was gone; there was only Maslova,” a street girl who looks at him, with a “bad glint” in her eyes, as at one of her customers, asks him for money, and when he hands it over and tries to say the main thing he came with, she does not listen to him at all, hiding the money she took from the warder behind her belt.

“After all, this is a dead woman,” thinks Nekhludoff, looking at Maslova. For a moment a “tempter” awakens in his soul, telling him that he will not do anything to this woman and he has only to give her money and leave her. But this moment passes. Nekhludoff overcomes the “tempter” and remains firm in his intentions.

Having hired a lawyer, Nekhludoff draws up a letter of appeal to the Senate and leaves for St Petersburg, to attend the examination of the case himself. But despite all his efforts the appeal is rejected, the votes of the senators are divided and the Court sentence is left unchanged.

Returning to Moscow, Nekhludoff takes with him a petition for pardon to be signed by Maslova, which he no longer believes to be successful; a few days later, following the batch of prisoners with whom Maslova is transported, he departs for Siberia.

Nekhludoff succeeds in persuading the transfer of Maslova from the penal ward to the political ward for the time of her transfer. This transfer improves her situation in all respects and her rapprochement with some of the political prisoners has a “decisive and most salutary influence” on Maslova. Through her friend Maria Pavlovna, Katusha realises that love is not about “sexual love” alone, and that beneficence is a necessary human “habit”, an “effort” which must constitute “the work of life”.

Throughout the narrative, Tolstoy gradually “resurrects” the souls of his characters. He leads them on the steps of moral perfection, reviving in them a “spiritual being” and raising him above the “animal”. This “resurrection” opens a new worldview for Nekhludoff and Maslova, making them sympathetic and attentive to all people.

At the end of the novel, Maslova’s party, having travelled some five thousand versts, arrives in a large Siberian city with a large transit prison. Nekhludoff had to collect all the mail that was coming from the centre of Russia at the post office (he had to be on the move all the time, so he would not receive any letters). Sorting through the mail, Nekhludoff finds a letter from Selenin, his friend from his youth. Together with the letter, Selenin sends Nekhludoff a copy of an official pardon for Maslova, under which hard labour is replaced by settlement in Siberia.

With the news of the pardon, Nekhludoff goes to see Maslova. At this meeting he tells her that as soon as the official paper has been received, they can decide where to live. But Maslova refuses Nekhludoff. During her time with the political prisoners, she became intimately acquainted with Vladimir Simonson, who was exiled to the Yakutsk region and fell in love with her. And although Nekhludoff was and still was the only man she truly loved, Maslova, no longer wishing to sacrifice Nekhludoff and fearing that she would spoil his life, chooses Simonson.

After excusing himself from Maslova, Nekhludoff goes round the prison cells with the travelling Englishman as his interpreter, and only in the late evening, in a tired and despondent state, returns to his hotel room. Left alone, Nekhludoff recalls all he has seen during the past months: that “terrible evil” which he saw and recognised in the offices of officials, in the courts, in prisons, etc.; the evil which “triumphed, reigned, and no possibility was seen not only of overcoming it, but even of understanding how to overcome it”. All this now rises in his imagination and demands clarification. Tired of thinking about it, Nekhludoff sits on the sofa and “mechanically” opens the Gospel given to him by the Englishman.

Nekhludoff stays up all night reading the Gospel, “soaking up like a sponge with water”, absorbing “the necessary, important and joyful things in the book” and finding answers to all his questions. Thus, concluding his novel, in its final chapter, Leo Tolstoy, through Dmitri Nekhludoff, expresses his view of Christian teaching. It is telling that initially, according to Taneyev, the novel had a ‘happy ending’, describing the life of the characters in England, but in August 1895 the writer decided to abandon this ending. In Tolstoy’s evangelical understanding, “‘Resurrection’ the rise of love from the tomb of the body”, “from the tomb of one’s person”.