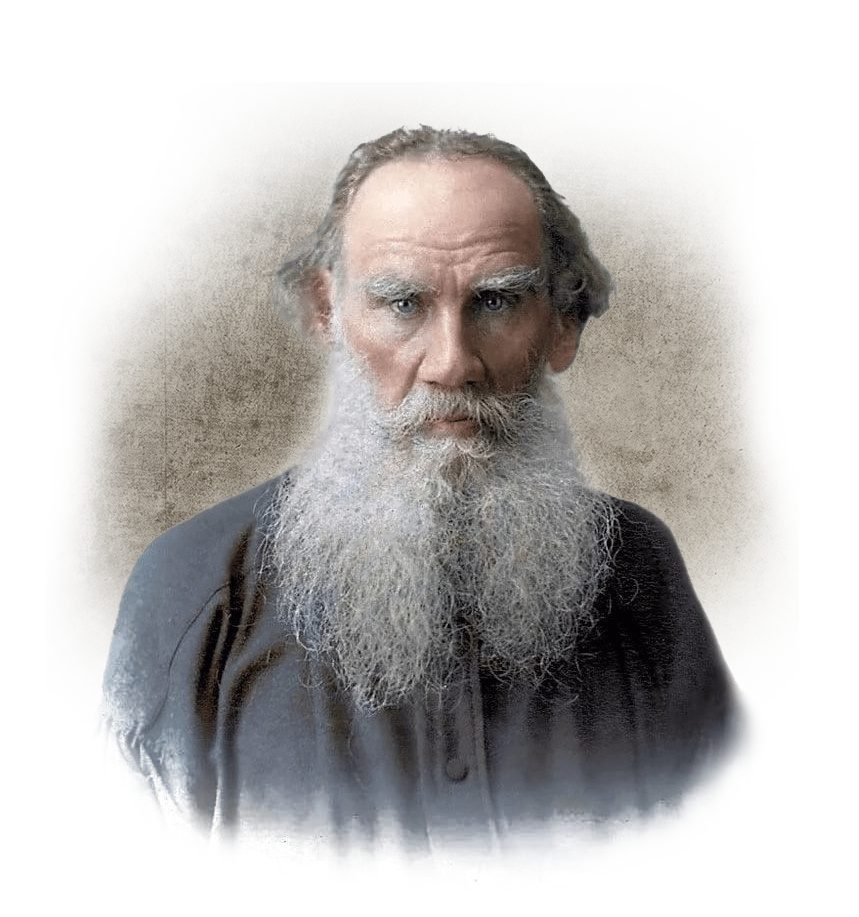

20.12.2022

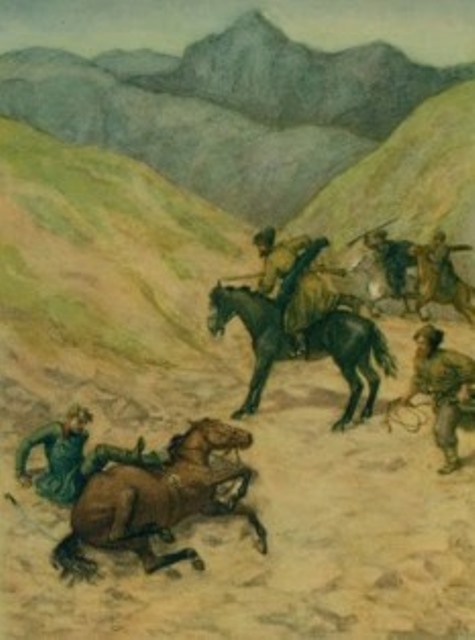

Tolstoy and his friend Sado accompanied the wagon train to the Grozny fortress, but they were moving very slowly. Bored, the friends decided to overtake the wagon and go a little faster. Breaking away from the others, the young men were ambushed by the Chechens. The story would have ended much worse if the Chechens had not planned to take their comrades alive and shoot them. The horses under Lev and Sado were frisky and were able to gallop away from the enemy. Unfortunately, of the mounted men escorting the wagon, a young officer was injured and his horse was shot. The animal fell over and crushed the young man, and the Chechens who approached hacked the rider to pieces. What happened happened sticks in the writer’s heart, and the story “The Prisoner of the Caucasus” was first published in the “Zarya” magazine in 1872.

The main idea of the story is a vivid contrast of a brave, intelligent and optimistic man with his fellow man – a passive, self-pitying, quick to give up and languid. One man stays a man in any situation, tries to find a way out of a terrible situation and, in the end, succeeds in getting out of captivity. The second character surrenders as soon as he is taken prisoner and only a miracle helps him to get out of the captivity alive. The moral of the work is: never give up, we only make our own desirable future with our own hands.

The “Prisoner of the Caucasus” is set during the war of the Caucasus (1817-1864), in which the Russian Imperial Army took part in the invasion of the Northern Caucasus. Officer Zhilin receives a letter from his mother, in which the woman calls him home. He is not allowed to go home alone as he could easily be ambushed, so Zhilin goes home escorting a convoy. Another officer, Kostylin, rides with him. The wagon train travels slowly, with stops, the day is hot and Zhilin proposes his fellow-traveller to go alone without an escort.

Barely leaving the wagon, the young men meet the highlanders. Kostylin leaves his companion and departs, and Zhilin is taken prisoner. Having brought the prisoner to the aul, one Tatar sells Zhilin to another – Abdul-Murat – the Russian officer now belongs to another “master”. Later it transpires that Kostylin has also been captured. Zhilin bargains for himself the right to decent food, to live with his fellow officer and to be free from the stocks at night.

The Tartars do not plan to kill the Russians – they demand that the officers write letters home demanding a ransom for them. Kostylin writes a letter demanding payment of five thousand roubles, while Zhilin purposely writes the wrong address so that the letter will not reach his mother for sure. He understands that the old woman does not have that much money and that if she tries to collect the ransom she will be completely ruined.

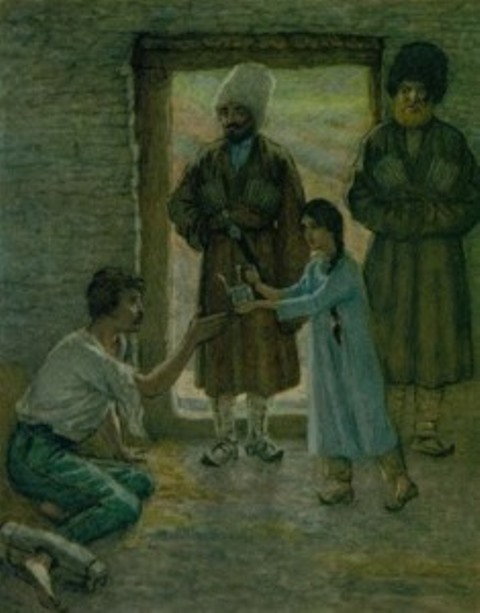

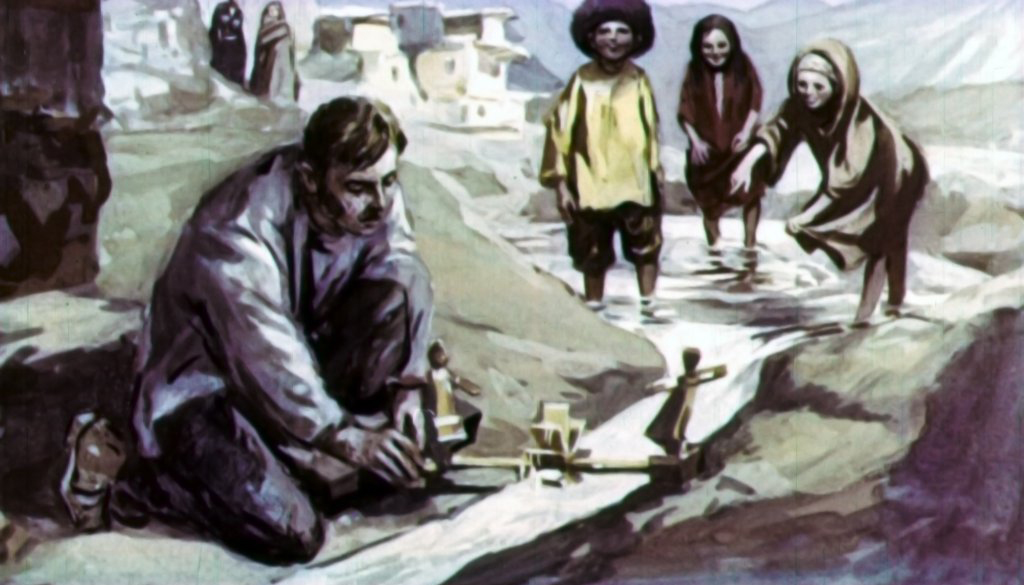

During the day the prisoners are allowed out, though they can only move about in the stocks. Kostylin prefers to sit and complain about life or sleep, while Zhilin spends his time in the open air, making dolls for the children. Thanks to his talent, the officer establishes an almost friendly relationship with Abdul-Murat’s thirteen-year-old daughter Dina. The girl is frightened of the prisoner, but at the same time she is interested in him. She happily plays with his dolls and even secretly brings him milk and flatbread. Meanwhile Zhilin not only helps the Tartars mend things and make toys for the children, but also looks around, planning his escape.

During the time that the officers have been living with the Tatars, Zhilin has gained favour with some of his “masters”. He is constantly mending and repairing something, and one day Abdul-Murat confesses to him that if it were not for the money paid for the Russian, he would have kept Zhilin for himself. Meanwhile Zhilin has dug himself a passage to escape. One day the Tatars arrive at their aul in a bad mood – their comrade has been killed. Many of the highlanders are angry with the Russians and say that the prisoners should be killed as well. Zhilin understands that they must flee and persuades Kostylin to dare to run away with him.

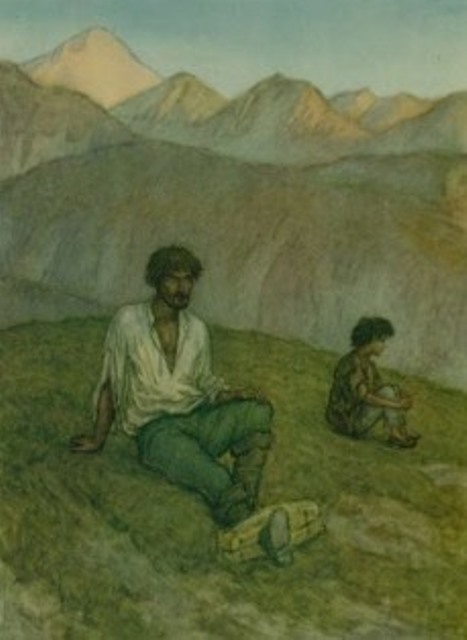

Kostylin hesitates to escape for a long time, but finally agrees. The captives trudge on in the darkness along the rocks, and the foreign-made boots given to them by the Tatars make it difficult to walk, and the young men are forced to walk barefoot. Exhausted, with shredded feet from the rocks, they continue moving towards their own, but Kostylin lags behind more and more. Inwardly Zhilin understands that he would move much faster alone, but he cannot leave his comrade. When Kostylin is completely exhausted, Zhilin carries him on his haunches.

However, in the forest the fugitives meet one of the Highlanders, who quickly calls for help, and the officers become prisoners once more. Now all the Tatars are angry with the Russians, and the men are thrown into a pit. They only feed them with unbaked dough, the stocks are no longer taken off, and there is talk of killing them. Abdul-Murat still resists public opinion – he still likes Zhilin a little and the money has been paid for him. Now there are conditions: if there is no ransom in a fortnight, the officers will be killed. If there is another escape, the same sad fate awaits the young prisoners.

Among all the angry Tatars, only little Dina treats Zhilin well. She continues to bring him flatbread, and soon tells him that the Russians are approaching the village and that the Tatars want to get rid of the prisoners without waiting for a ransom. Kostylin despairs irrevocably, whines incessantly and falls ill.

Zhilin understands that only Dina can help him now, and asks the girl to bring him a long pole. He assumes that the girl will not have the courage, but one night she brings the stick and lowers it into the pit with the prisoners. Realising that the last time they were only caught by the Tartars because of Kostylin, Zhilin nevertheless offers his unfortunate companion to run away with him. But Kostylin is so despondent that he can hardly turn over, and escape is out of the question.

Dina helps Zhilin out of the pit, gives him some bread for the journey and bids him farewell in tears. Exhausted and in the stocks, the officer makes his way with great difficulty to his men, almost ending up in another ambush by the Tatars. After a while Kostylin is also freed – the Tatars obtain a ransom for him and release him. However, by this time the captive Kostylin is almost dead.

The meaning of the title of Leo Tolstoy’s story “The Prisoner of the Caucasus”

In his work Leo Tolstoy acts as a narrator, telling the story of a man, brave in heart and strong in spirit. His parable-fable proves that man is a creator of his own happiness, and each of us gets what we deserve.

The title of Tolstoy’s story is a reference to Pushkin’s poem of the same name. However, apart from some common motifs, Tolstoy’s The Prisoner of the Caucasus has a profound meaning of its own. Moreover, the meaning of the phrase “Prisoner of the Caucasus” can be considered from several angles.

The first meaning, the most obvious: a captive of the Caucasus is any captive of a person. In this case, it is an officer taken prisoner of war in the Caucasus.

The second meaning of the title “Prisoner of the Caucasus” is embedded in Kostylin’s character – he is a prisoner of the Caucasus and the prevailing circumstances. He is and will remain a prisoner in essence, as he does nothing to become free, to improve his situation, to fight for his life.

Zhilin is also a Caucasian prisoner, but not only because he is a prisoner, but also because he cannot “escape” from the Caucasus in any way. He has tried to go to his mother and possibly find a bride in his native land and stay there. But he is taken prisoner, and returns to the fortress, thinking that the Caucasus must be his destiny.

The highlanders themselves are prisoners of war. They cannot give up their homeland to outsiders, they have to fight for their freedom and kill people – even those they sympathise with. Even Dina, a kind little girl, is forced to submit to her family’s authority and continue to live the way things are done in her village. All the characters in the story ‘The Prisoner of the Caucasus’ are essentially prisoners of the Caucasus – each in his own way, but captive to the mountains and the circumstances, despite their personal characteristics and character.