20.12.2022

As a young man, Leo Tolstoy used to drink and gamble away at cards, remembering, however, to keep a “journal for weaknesses” in which he berated himself for his youthfulness and wasted life. Then he would go to another game of corkscrew.

Settling down, he became a calculating landowner, owner of eight thousand dessiatinas, with whom the landowner Shenshin (Athanasius Fet) was desperately competing, and who was desperately envied by Dostoevsky, a townsman who only got out of debts of his late brother Michael and the bondage of his own publishers on the eve of his death.

Towards the end of his life Leo Tolstoy has become indifferent to the benefits of the earth; the desire for wealth was considered worthless, and his royalties gave the Dukhobors, about to emigrate from the persecution of the government in Canada.

Cult of the ancestors

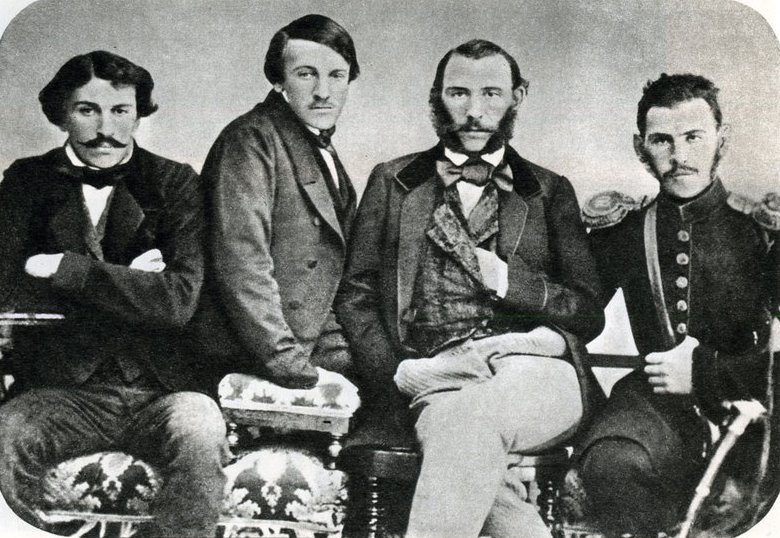

People who knew Lev Nikolaevich and his family, his ancestors, believed that more important than any inheritance and succession for him was the true cult of ancestors. It was not without reason that the writer considered himself “the product of previous people”, among whom his paternal grandfather and maternal grandfather stood out.

Indeed, in his youth, before his marriage, Leo Tolstoy behaved as if he sought to imitate his paternal grandfather, Ilya Andreevich Tolstoy. Ilya Andreyevich was a rather limited man, but cheerful and gentle. He owned 1.2 thousand serfs, 4 thousand dessiatinas of land, and 3 distilleries, which supplied wine to the Russian market. This legendary sybarite and moth easily sent his servants to the south of France for fresh violets, and to Astrakhan for real sterlet. He sent his laundry to Holland (as did the Kurakine princes a century later, who were convinced by bitter experience that Russian laundresses had never learned how to work with expensive fabrics). Having squandered half a million of his fortune, Ilya Andreevich Tolstoy became governor of Kazan at the end of his life. The young Tolstoy was struck by his grandfather’s natural ability and always ready to live life to the fullest, and it seems that it was Ilya Andreevich who became the prototype of the old Count Tolstoy in his novel War and Peace.

Tolstoy earned more than Ivan Turgenev and strongly disagreed with him that a true artist cannot engage in material matters.

Having become a family man, a solid and famous writer, Leo Tolstoy was universally believed to resemble his maternal grandfather, Prince Nikolai Sergeyevich Volkonsky, for whom the true god was order (in his novel War and Peace he served to create the image of the old Prince Bolkonsky). Lev Nikolaevich’s great-grandfather, Nikolai Ivanovich Gorchakov, the owner of a huge fortune, was also remembered as an extremely stingy man. His favourite pastime, to which the old man Gorchakov could indulge for days, was counting the money in his cherished casket. The blind old man pored over crumpled papers, unaware that half of them had long since been replaced by newsprint.

In April 1847 the Tolstoy brothers and sister divided the inherited property of their parents. Leo got the villages Yasnaya Polyana, Yasenki, Yagodnaya, Mostovaya Pustoshcha of Krapiven county and Malaya Vorotynka of Bogoroditsk county of Tula province. In all, he received 1.47 thousand dessiatinas of land and 330 souls of men. To “supplement the benefits” his brothers gave him 4 thousand roubles in silver.

The land at Yasnaya Polyana was “fertile, the bread and meadows are average, the wood is woody, the peasants are in the field”. In other words, a mediocre estate. In addition, it was mortgaged by his parents in the Board of Guardians. The first thing Leo Tolstoy did was to try to get the estate out of the trusteeship and into his own ownership. And at the same time he was concerned with a project of afforestation in Russia and liberation of the Yasnaya Polyana peasants from serfdom. He seriously thought of serving in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and opened a school for the children of peasants.

Predictably, all his efforts failed and his projects remained on paper. What saved the day were the maps. Living “carelessly, without service, without occupation, without purpose”, he gave himself wholly to his “cursed passion” for the game. The losses became more and more impressive: 850 roubles, 3,000, 5,000 roubles. To pay off his debts, he sold Malaya Vorotynka for 18 thousand roubles and Yagodnaya for 5.7 thousand roubles. At the same time he sold thoroughbred horses at fairs for a mere pittance and threw money at the most expensive restaurants and the most fashionable tailors.

Yasnaya Polyana had fallen into complete disrepair by this time. It was not only the inexperience of the young landowner that was to blame, but also the “shameless robbery” by the manager and the headman. Unable to cope with the thieves, Tolstoy returned to the card table. To no avail, of course.

For eight years he kept asking the question in his diaries: ‘What have I been assigned to? Between maps, horse shows and carousing, he made time for his own literary pursuits. But only 7 March 1851 he wrote in his diary: “Occupation for tomorrow … novel”. And began to write, carried away – and brought to the end of the story “Childhood”.

And already 2 July 1852 Tolstoy wrote a letter to the editor of the journal “Contemporary” with a request for the publication of “Childhood. Secretly tormented, rushing from despair to hope. He decided: to publish – then encourage him to write, and then his whole life will change, and failing that – to burn everything that has already been started. The manuscript was accepted, and Tolstoy rejoiced “to the point of foolishness”. The feedback from the editors was flattering, and the debutant responded adequately – in categorical form, he demanded a fee: at the time he was in dire need of money. From his first steps in his new field, Leo Tolstoy regarded writing not as a lordly whim, but as a profession with all its economic consequences. The correspondence with publishers revealed that Sovremennik does not pay for the debuts, but Nekrasov promised Tolstoy for his subsequent works “the best fee” – 50 rubles in silver for the printed page.

Family man and writer

Leo Tolstoy began his family life with the correction of his distressed state, aided both by his growing fame and the writer’s royalties. He began to buy up land around Yasnaya Polyana, and later in the Samara steppes. A few years later the 750 dessiatinas his parents had left after their card losses increased sixfold.

In the 60s Leo Tolstoy was a rich and prudent landowner, keeping his farm in perfect condition. About three hundred pigs, dozens of cows, hundreds of thoroughbred sheep and birds. Plus an apiary, a distillery and a huge orchard. He started a creamery, the production of which went on the Moscow markets at 60 kopecks per pound. Having got rid of a confused and inept manager, he entrusted the office and the till to his most serious assistant – his wife.

But the main source of income remained, of course, literature. While Dostoevsky managed to extract from magazine editors and book publishers 150-250 rubles per page, Lev Nikolayevich got 500 rubles per page and started to prepare its separate publication himself. He personally accounted for the printer’s expenses, controlled the publisher’s activities, the sale of books and their condition and movement in the warehouses. He calculated the circulation, the cost of a single copy and “his peace of mind”, which cost him, as he thought, an extra 5%. According to Tolstoy’s calculations, the publisher received 10% of the publication, the booksellers – 20%.

At that time Leo Tolstoy did not forget for a minute about his family, which already had 13 children, and staff to serve the family – teachers, governesses (who were paid monthly 30 rubles or more), servants, stablemen, coachmen, etc. His janitors and cooks received 8 roubles in cash each month, and the Earl paid pensions to the elderly.

The landlord and the writer

In 1892 Leo Tolstoy left all his possessions to his wife and children. He left himself only the essentials for his journey into eternity. Operating with sums of money which neither Gogol, nor Dostoevsky, nor even Turgenev could dream of, Leo Tolstoy entered into agreements and transactions with publishers as a tough, unyielding and utterly pragmatic author. No agreement was out of the question if, for example, it did not provide for the payment of royalties in advance, in advance. Leo Tolstoy dictated the amount of fees, renounced his previous obligations, if he was dissatisfied with the conditions or the calculation of the dividends due to him.

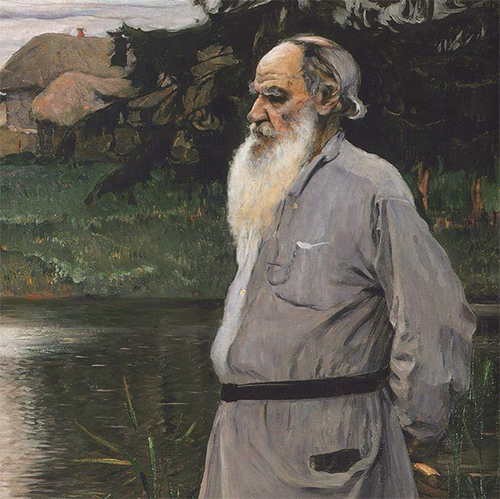

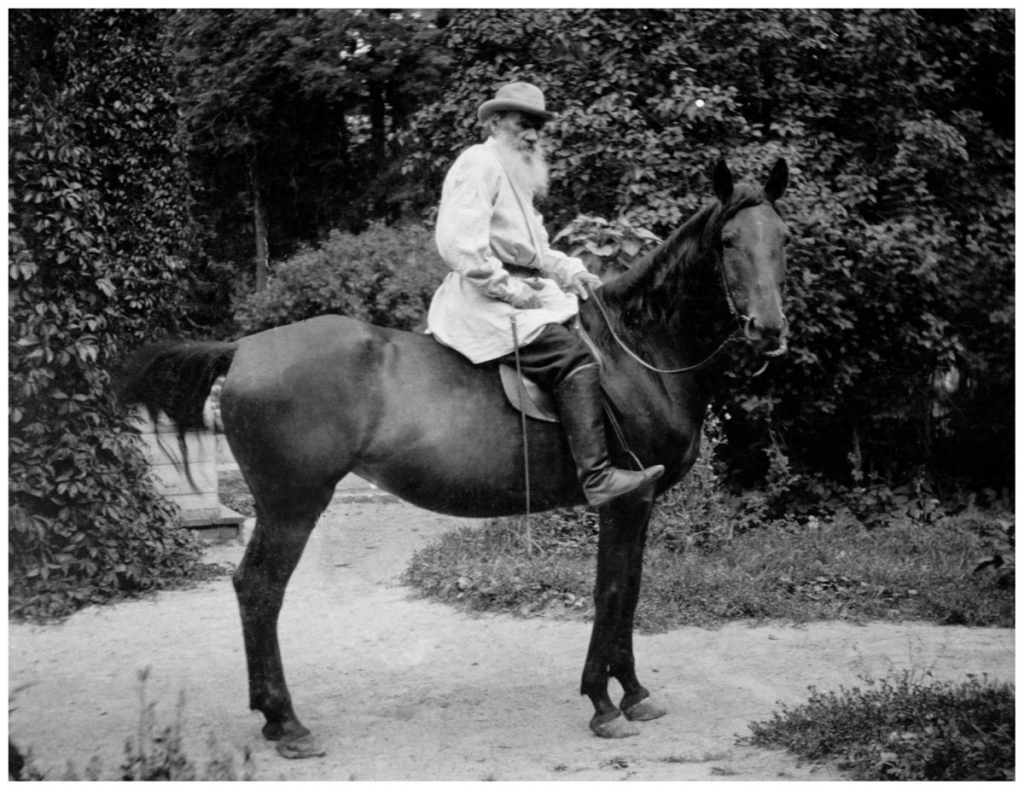

The Hermit

The writer’s spiritual search began in the 80s, which led to a reassessment of many of the criteria which had previously guided him. Life in conditions of surplus material values started to seem more unbearable to him than life of any vagabond. His relatives have recalled his mother, who before marriage was prone to shocking gestures: she could, for instance, give a companion friend tens of thousands of roubles as a dowry. The late mother was, of course, nothing to do with it. Tolstoy changed radically, and it was an existential change – in the depths of his soul, at the level of his outlook. Whereas Fet, for example, after reading the sombre Schopenhauer, wrote the lightest poems of his life, Leo Tolstoy took from the German only an aversion to life in all its “ugly” manifestations. In 1883 he gave his wife power of attorney for all the property affairs, and nine years later, “signed and donated what he had long since considered his own. The entire property, valued at 550,000 roubles, went to his wife and children by deed of partition.

His own annual income in those last years ranged from 600 to 1.2 thousand roubles – that was the fee he received from the Imperial Theatres for the play “The Fruits of Enlightenment”. In addition, he was saving about two thousand roubles for a rainy day. He was already living out of this relationship, perhaps occasionally recalling Voltaire, whom he generally disliked: “One does not go to eternity with great baggage”.