21.12.2022

A chronicle of the illness and death of a judicial official, preceded by the story of his life. A one-of-a-kind work about how one experiences the approaching end, what psychological tricks one uses to dodge the realization of its inevitability, and how one finally becomes aware of death – the most important thing in life that completely changes one’s understanding of life itself.

When was it written?

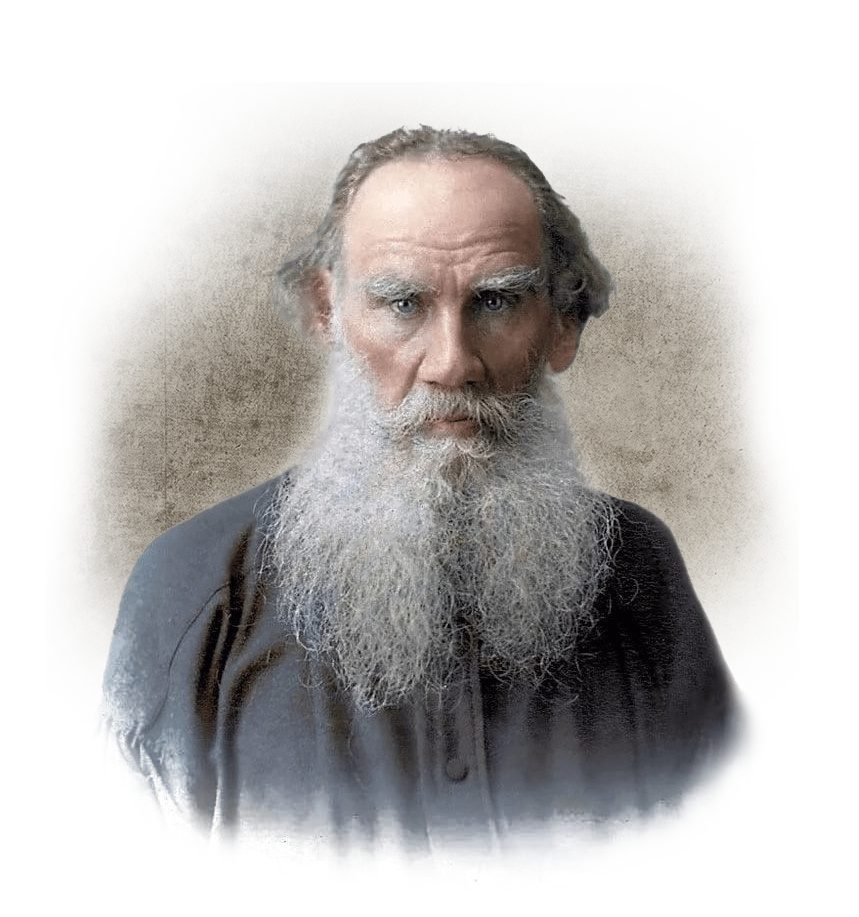

The early 1880s for Tolstoy – a time of “spiritual revolution”: he reconsiders his own life, formulates his creed – sets out the ideas that will form the basis of Tolstoyism. The idea for the story of “the simple death of a simple man” dates back to 1881; its original title was “The Death of the Judge”. At the same time Tolstoy was preparing his Confession for publication, finishing his main religious and dogmatic works – “An Inquiry into Dogmatic Theology” and “The Connection and Translation of the Four Gospels” – and beginning work on the treatises “What is My Faith?” and “So What Shall We Do?”.

The idea for a novel remains unrealised for a long time; on 27 April 1884 Tolstoy wrote in his diary: “I want to start and finish a new story: either the death of a judge or the notes of a madman”; from later notes it follows that some outlines of the story already existed by that time. The title ‘Death of Ivan Ilyich’ is first mentioned in a letter from Sophia Andreevna Tolstaya to Tatiana Kuzminskaya of 4 December 1884: she reports that her husband was reading an excerpt from a new story; ‘he is writing, as if he has experienced something important’. The original version of the story was a diary of Ivan Ilyich himself, later (around the autumn of 1885) Tolstoy moves to a narrative on behalf of the author. The final version of the text is dated March 25, 1886.

How is it written?

“The Death of Ivan Ilyich is one of the pinnacles of Tolstoy’s introspection: the author traces not only changes in emotions and moods, conscious or unconscious motives for actions, but even the smallest physiological sensations. The tale marks a turn towards “late Tolstoy”: the author seems as if he is trying to tone down the beauty of the verse in favour of didacticism. The language becomes drier and more minimalistic: in the words of the literary critic Sergei Bocharov, “the author’s word has begun to shrink and simplify, to shrink, it has begun to wither and at the same time to sharpen to the extreme”. The rhetorical figures in The Death of Ivan Ilyich are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s treatises (which were partly created at the same time as the novel), but, unlike his publicistic works, the author gives no direct answer to the character’s “why?” questions.

What influenced her?

Tolstoy’s acquaintance with Ivan Mechnikov, prosecutor of the Tula court, and the story of his subsequent illness and death. The deaths of those close to him, Ivan Turgenev (1883) and Prince Leonid Urusov (1885). Tolstoy’s own reflections on the meaning of death, which run through many different texts – from his early diary entries to the scene of Prince Andrei’s death in War and Peace, from the story Three Deaths to the Confessions and the religious-philosophical writings of the 1880s.

How was it published?

In 1886, in the next, twelfth part of The Works of Count Tolstoy, published by Sophia Andreevna Tolstoy.

How was it received?

In the first reviews that appear in letters and diaries of contemporaries, the story is regarded as one of the pinnacles of Tolstoy and world literature in general.

“No people, no place in the world has such a brilliant creation,” Vladimir Stasov wrote to Tolstoy on April 25, 1886. – Everything is small, everything is shallow, everything is weak and pale in comparison with these 70 pages. Peter Tchaikovsky July 12, 1886 writes in his diary: “I have read ‘Death of Ivan Ilyich’. More than ever, I am convinced that the greatest living writer-artist ever and anywhere – is Leo Tolstoy. He alone is enough for the Russian man not to bow his head ashamedly when all the great things that Europe has given to mankind are counted before him”.

The degree of enthusiasm around the new novel is such that Nikolai Leskov has to stand up for contemporary writers whose talent, by all accounts, is not comparable to Tolstoy’s greatness. In his article “On the Kufel Man and Other Things” he writes:

“While praising the count in a worthy manner, some of the critics have tried in several ways to reveal their own, particularly contemptuous attitude towards all other writers who “also write” and are also “called writers”.

It reminds one of Pismsky’s heroes, who, riding in a frayed coat, says contemptuously to her:

– You bastard! And you are also called a fur coat”. For Leskov, the main content of the story is how indifferent “the so-called educated people of Russian society” prove to be to other people’s grief and how “above all this insensitive crowd rises high and stands majestically… “Kufelny man”, who is the most sympathetic, because he lives, knowing that he “will have to die himself!” Nikolai Mikhailovsky, for his part, believes that the new story “is not the first number either in artistic beauty or in the strength and clarity of thought or in fearless realism of writing,” but such restrained reviews remain in the minority – the authority of Tolstoy as a writer by this time is indisputable, and if his religious and philosophical works (which, however, under the censorship ban) provoke fierce controversy, the advantages of the new story challenged by almost no one.