24.12.2022

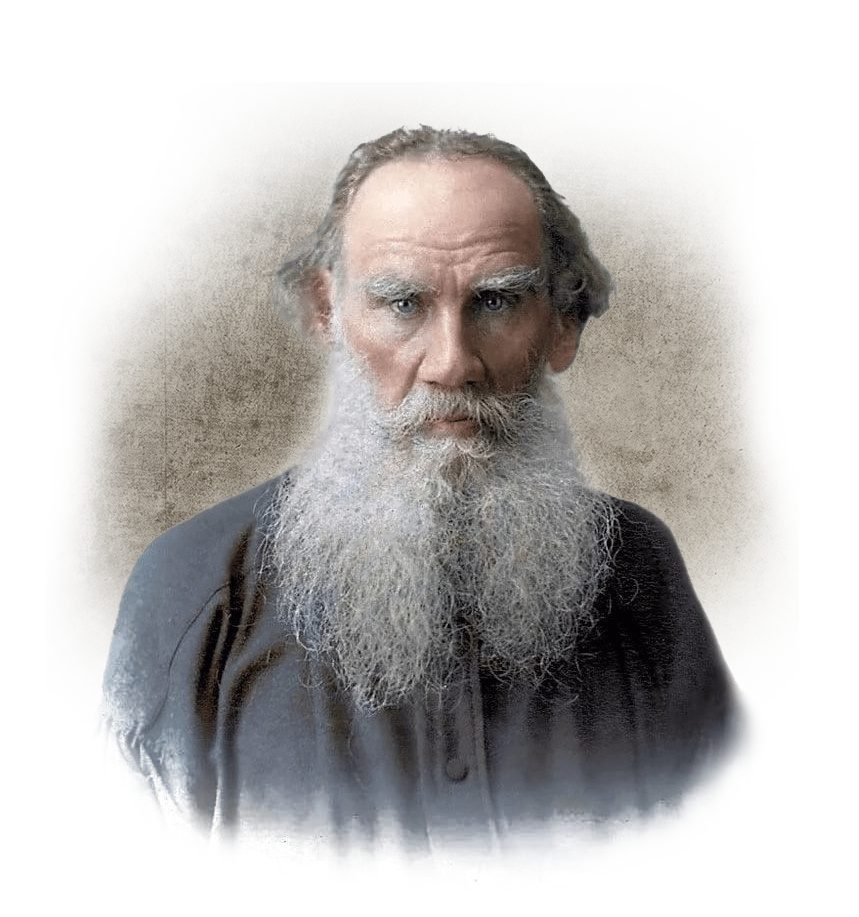

“What is Art?” (1897) is an essay by Leo Tolstoy in which he argues against numerous aesthetic theories that define art in terms of a theory of relation, truth, and especially beauty. According to Tolstoy, art at the time was corrupt and decadent, and artists were misled.

General points

The essay develops the aesthetic theories that flourished in the late eighteenth century and during the nineteenth century, thus criticising the realist position and the existing relationship between art and pleasure. Tolstoy, in addition to the existing theory, stresses the importance of emotionality in art, the importance of communication leading to the rejection of bad or fake art, as they are harmful to society as they disrupt people’s ability to perceive art.

Contents of the essay

According to Tolstoy, art must create a certain emotional connection between the artist and the audience that “infects” the viewer. Thus, real art requires the ability to bring people together through a channel of communication (hence the importance of clarity and sincerity). This aesthetic conception led Tolstoy to expand the criteria specifically for a work of art. He believes that the concept of art encompasses any human activity. Tolstoy offers the following example. The boy who experienced fear after an encounter with a wolf later narrates so that the experience, infecting his listeners, makes them feel in danger and what the boy experienced. And this is a perfect example of a work of art.

Art is postulated and fixed by Tolstoy as a branch of activity in which, on a par with war, human lives are directly spent. Art becomes a branch of human activity that is sponsored by an exorbitant amount of subsidies, estimated at millions, given the existence of a branch of public education financed much less. Information about the seemingly daily opening of theatres, museums and exhibitions floods newspapers, books and lyrical works.

Art is an activity which requires an exorbitant investment of human life, from the time devoted to learning the skill of rapid-fire finger-picking on the keys, to the ability to portray all the phenomena one sees on a canvas. For want of a great outlook on life and for want of an opportunity to live that life, people of art in their own stupefying pursuits become incapable of appreciating the seriousness of the surrounding reality.

Tolstoy recalls a rehearsal of an opera which he saw in which, despite the seemingly perfect performance, the choristers and chorus girls were subjected to moral humiliation by the conductor. Such a person, writes Tolstoy, subjected to such humiliation, remains inherently miserable, physically and morally disfigured. Such a person learns to obey orders. Such a person is at the mercy of the oppressor, who knows that the mutilated man is no longer good for anything except “trumpeting and walking with a halberd in yellow shoes. What makes one endure this kind of abuse? The “sweet” life or the illusion of such a life, the fear of being deprived of luxury, of visiting the finest halls, of associating with the best figures of the same art provokes the emergence of such mutilated lives, unable to want anything other than the “sweetness” given them in an environment of rudeness and humiliation.

“Can it happen that art is a harmful thing?” – Tolstoy asks. However, a harmful thing that takes away and takes away. It is not giving back to those who undergo aesthetic benefits and pleasures. The artist does not do his job by himself, the ballet dancer does not do his performance by himself, both need the help of the other, just like the rest of the “high” figures. The other, in turn, sometimes does a humiliating and dirty job without the subsidy from the government given to the person above, and without a luxurious existence. All this is taking place in an era in which some sort of consciousness, albeit vague, of the equality of all people has arrived. Can art, in the person of the artist, force a free man to work as a forced labourer? Art redeems violence, art gives violence the status of a legitimate act, which becomes its inalienable attribute.

Lev Nikolaevich defines the place of art this way: “Art in all its forms borders on the practically useful, on the one hand, and on the other, on failed attempts at art. The challenge here is to distinguish one from the other. By defining art as a manifestation of beauty, you leave large tracts of empty space, but the person who does not know, describes the overriding attribute of art in this way – the recognition, the expression of beauty. If this is true, what is beauty? How is it defined, being the content of art? Beneath the universal opinion that the concept of ‘art’, or in the latter case, ‘beauty’, is a concept that is clear and universally accessible, there is a deep misunderstanding of the subject matter, of the terms which are key in this discourse. Despite the existing works of reasoning about the meaning of ‘beauty’ or ‘art’, questions about their essence still remain open. The meaning of the word ‘beauty’ remains a mystery after 150 years of deliberation by thousands of scholars.

Baumgarten, the founder of aesthetics, defined beauty as the perfect, absolute cognisable sense. Beauty is the object of aesthetic cognition. Writers Schütz, Sulzer and Mendelssohn, on the other hand, define the purpose of art as good. According to Winkelmann’s essay, the law and goal of all art is only beauty, completely separate and independent from the good. Thus, time after time, giving definitions of beauty and judgments about it, Tolstoy reveals the contradictions and inaccuracies existing in this case. The author tries to clearly demonstrate the existing contradictions regarding the leading questions about the theme of our conversation – the theme of art. As a result of the quotations and opinions cited, one may conclude that the definitions of beauty ever given in aesthetics can be reduced to two basic views. “Beauty is something that exists in itself…beauty is a kind of pleasure that we derive without the goal of personal gain. If we agree with these ways of defining beauty, we agree only with the act of recognizing as “good” that which is pleasing to the known circle of people. In following the way that the history of aesthetics has proposed in defining the term “beauty,” we miss the very essence of the phenomenon, which is essential to understanding it. If we have a sincere desire to capture the answers to the questions posed above, we would do well to consider the activity at hand as such, not in relation to the pleasure we derive from it. Recognising pleasure as the goal of our activity is a false definition of this activity. This is what we endure in relation to art.

Beauty or individual views on the ‘aesthetic’ are not the basis for a definition of art. What art brings us is not the pattern of the art form.

What is left in the definition of art after the knowledge that beauty is not the rightful foundation of art? The next definition put forward is a physiological-evolutionary one. “Art is the manifestation outwardly, by means of lines, colours, gestures, sounds, words, emotions experienced by man”. Definition of art through experience. However, this definition too has inaccuracies and is not suitable for a true definition of art in its essence. In this definition, the revelation of pleasure or the experience of the human being from the outside is key. In order to define art we must abandon our view of art as a means of our own enjoyment, and try to look at art as one of the conditions of human life. In attempting to do so, we cannot help but discover that art is one of the means by which people communicate with one another.

Art acts as a word which conveys the speaker’s thought. Only if with a word the speaker conveys a thought, a thought here is some logical metaphysical guise of a word, in art the “speaker” conveys a feeling. There is an empathic effect at work in art. A person, due to his or her own physiological peculiarities, is capable of feeling empathy towards another person. With respect to art, this feeling of empathy is also expressed as empathising, feeling into the other person’s emotion. It is possible, through art, to convey a certain emotion – laughter, sadness, fear, sadness – just as it is possible to do in a personal act of communication. Just as we smile when we respond to the smile of our interlocutor, we smile when we see a work of art in which the smile is “embedded”. “The smile” of a work of art is recognisable to us in the same way as the smile of a real person. Art is based on people’s ability to be energised by the feelings of others.

The activity of art is as important as the activity of speech. The act of art, the act of communicating a common emotion, humanises man as much as the act of speech. This view of Tolstoy on the role of art may also be linked to his Christocentric views and attitude to religion in general. A necessary condition of religion is synodality, inclusion, undergoing the experience of such inclusion with others, with neighbor. The same is true of art, which preserves the experience of communion with a common feeling. Not all of the human activity that conveys feeling can be called art, but only the activity to which we attach special significance. A special importance was attached by man to activities which were derived from religious consciousness. The history of ethics in its diversity, in its variety of different conceptions of true art, is linked to the transforming religious consciousness. Therefore, the ancient notions of beauty can be in conflict with the modern conception of beauty, just as other categories of art can be in conflict.

If, as it was concluded earlier, art is a human activity with the purpose of conveying the highest and best feelings to men, how has this activity, based on a profound religious feeling, been transformed into a cause where man puts his own pleasure first? “Ever since the higher classes of the Christian nations lost faith in ecclesiastical Christianity, the art of the higher classes became separated from the art of all the people, and there were two arts: the art of the people and the art of the domineering” – writes Tolstoy. Where is the basis by which we dare to make the logical mistake of defining art as true or false and to argue about the moment of the transformation of art as the transmission of a deep religious feeling into an activity based on pleasure? The key point here is committing the logical error of definition. Through this error, it is as if we are taking art, which exists outside our field of vision, outside the field of vision of the man of Russia, out of the brackets. For besides art, which we could touch in one way or another, other planes were developing, the art of other peoples, where such a transformation may not have been observed, and it is not a phenomenon with the quantifier of universality. Lev Nikolayevich gives this answer in his work: “…not all humanity, or even a considerable part of it, lived without true art, but only the upper classes of Christian European society, and then, for a very comparatively short period of time”. Thus, it turns out, the loss of ‘true’ art is directly linked to the spiritual crisis that once erupted in European society, which led to the development of a different categorical system, which allowed a ‘different’ art to emerge, an art that was not true.

However, this relatively short period was enough to corrupt the class which used art. The misrepresentation of art was made possible by the false assumption that the art of the upper classes was all art, that art was universal. In this extremely short period of history lies the reason why the side of art, which only brought pleasure to a certain circle of people, the upper classes of the European world, acquired a generally recognizable status.

The faithlessness of the upper classes had a necessary moral consequence. Art became impoverished in content behind the recognition as art of the false, behind the recognition as art of that which brings pleasure. Whereas true art conveyed feelings new, unexperienced by men. “There is nothing more old and hackneyed than pleasure; and there is nothing more new than the feelings arising from the religious consciousness of a known time.”

As opposed to human desire, as opposed to pleasure and enjoyment, we have a variety of feelings, the experience of “feeling” which we can only get from religious consciousness. The variety of these feelings is infinite. With the loss of true art in its religiosity, art, too, ceased to be popular, becoming an attribute of elitist circles. The feelings capable of being experienced by a man of luxury, a man of the upper class who does not know labour, the maintenance of life, are far poorer and scarcer than the feelings of a man of the people. The feelings of the upper class could be reduced to pride, lust for sex and longing for life. This is vividly exposed in the works of “art” of the time. Behind the illusion of a diverse spectrum of feelings there are only three lowly experiences. The pride in the first stage of the separation of high class art from popular art was expressed with all its power during the Renaissance, when the main subject was the glorification of the mighty. Then an element of sexual lust joined art. Later came a sense of longing for life, which is revealed in the works of Byron, Heine and Leopardi. Such a sense of longing for life could also be linked to Heidegger’s sense of “homesickness”.

With the division of art and the faithlessness of the upper classes, art also became pretentious and obscure. Whereas the national, universal artist endeavoured to expound an idea or sentiment in an intelligible way for all, the artist who composes for a small circle must make use of exclusive techniques which are only understandable to this small circle. Thus arises the alluring mystery of art, the veil of the hidden, of that which the man of the people has no power to touch. The meaning remains hidden for him, because originally created not for him. As examples of such a phenomenon, Tolstoy cites the works of Verlaine, Mallarmér, Baudelaire and others. Under the pretext of conveying a certain mood, inaccuracies and false comparisons are piled up. The mastery of eloquence is lost. Art appears as a kind of amusement in which non-existent absurdities are invented. The content becomes narrower and narrower. Beyond the limitation of the content the search for new forms with which to hide the meagerness of the essence begins.

The same is true of painting. For example, Lev Nikolaevich cited an extract from the diary of an amateur painter who attended an exhibition in Paris in 1894. In this extract he expresses his own perplexity and indignation. “There is no drawing, no content, the colouring is most unbelievable…the drawing is so indefinable that sometimes you cannot understand where the hand or head is turned”. Thus Tolstoy records a similar impoverishment behind the appearing pretentiousness and obscurity in drama, in music and in ‘art which would seem to be more equally understood by all. These areas of art, which seemed to be more than all equally understandable to all, Tolstoy calls the novel and novella.

By becoming poorer in content, by losing form, art has been replaced by its imitations. Perhaps in this discussion of imitations replacing art, it would be appropriate to remember Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra. With Baudrillard, however, art is already simulacrum, but there is a similarity in the way of thinking, in my opinion. Why, with the impoverishment of content and the loss of form, was art replaced by a simulacrum? If a popular artist creates a work of art guided by a strong feeling, then a person who creates for a small circle “makes” something for the entertainment of that same circle only, and not out of his own need to express what he feels. In the absence of his own need to create, and having the order to produce, the artist becomes driven by such principles: borrowing, imitation, amazement, amusement. Tolstoy also cites three conditions for the existence of fake art: considerable remuneration for artists for their work, art criticism and art schools. With the split of art into folk art and art of the upper classes, religiosity is devalued and indifference is encouraged. Art becomes a profession, losing its own sincerity. The artist, living as a professional, has no choice but to invent his or her own subjects. To invent in order to earn his livelihood, to invent for a certain order of a higher class. In order to fulfil his orders, the artist learns, absorbs what has already been written in order to borrow and reproduce it. With the emergence of criticism as a professional path, ordinary people are “liberated” from criticism. Criticism praises fictional works, which are reasoned, not moved by feeling. There is also the question of the possibility of teaching art in schools, for art is the transmission of a particular, experienced feeling. In what ways could one teach to transmit this kind of feeling? The school can only teach how to convey feelings experienced by others. In piling up false art, in creating the conditions and basis for its existence people have forgotten how to perceive true art, they are mesmerized by illusion.

The contagiousness of art is the difference between real and fake art. A work of art can be said to be a work which when you read, hear or see it, gives you a unique feeling which is in line with that of its author. Counterfeit art is incapable of this. When you undergo this feeling, you merge with the artist, feeling that you are a part of his or her own art. One is charged with the author’s state of mind. “The stronger the contagion, the better the art as art, not to mention its content, that is, regardless of the dignity of the feelings it conveys.” The contagiousness of art is also determined by a number of conditions: a greater or lesser degree of transmitted feeling; a greater or lesser degree of clarity in transmitting feeling; the degree of sincerity of the artist, the strength with which the artist himself experiences feeling. The absence of one of the conditions defines fake art.

Tolstoy sees the destruction of the established division in art in religious unity. With the conscious recognition of religious consciousness people split will be abolished. In the unity of religious opens the way to the verification of the general, brotherly art. With such art, feelings that do not agree with religious consciousness will be discarded. Thus art will cease to exist as a means of coarsening and corrupting men, but will become a means of moving towards the good. “The reason for the emergence of real art is the inner need to express accumulated feeling, just as for a mother the reason for sexual conception is love. The cause of fake art is self-interest. If the consequences of true art are consequences of love, then the consequences of fake art are consequences of depravity, insatiability and human weakness. In the future, however, art will be works of art leading to fraternal unity, capable of uniting all people. Lev Nikolaevich spent 15 years reflecting on art. He concludes by noting the interrelationship between the development of science and art. Art, as a transformer of science, is also capable of absorbing false truths, so it is important to develop science in the right direction. Art should give universal status to the sense of brotherhood and love of one’s neighbour. With the destruction of the divide and the unification of mankind in a single feeling the national art will educate the people. The purpose of art is the transfer from “the realm of the intellect to the realm of the feeling the truth that the good of the people is in their unity and the establishment in place of the reigning violence now of the kingdom of God, love, which seems to us all the highest goal of mankind.