21.12.2022

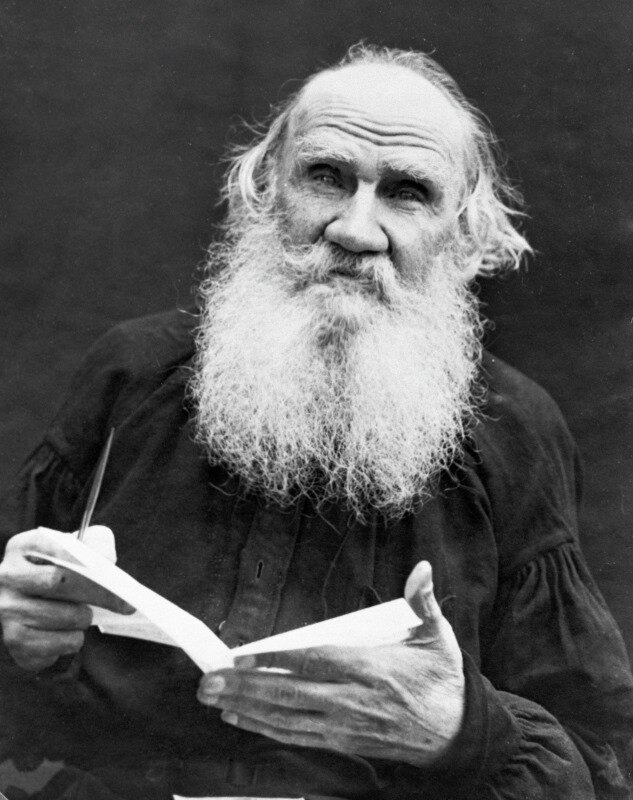

Leo Tolstoy wrote The Kreutzer Sonata in 1890. It raises the issues of marriage, family, attitude towards a woman. The main character who could not build his family life properly, eventually turns out to be a murderer. The composition of the story is important: it is constructed as a monologue of the protagonist turned to his fellow passengers on the train.

The protagonists

Pozdnyshev is a middle-aged landowner, a man deeply disappointed in love and marriage.

Other characters

Mrs. Pozdnysheva – the main character’s wife, a young woman who has become a victim of her husband’s jealousy.

Trukhachevsky is a musician, a violinist, a young attractive man who has become fascinated by Mrs. Pozdnysheva.

The narrator is Pozdnyshev’s chance fellow traveller, to whom he tells his life story.

Chapters 1-2

In the train carriage a lively conversation ensued between the bored passengers about women, marriage and love outside marriage. The lady wondered how they used to “marry just anyone and suffer all their lives”. She thought that people could not, like animals, simply mate with each other and it was quite wrong to “live with a man when there is no love”. The old menacing merchant assured her that “a woman is a wretched vessel” and no one is interested in her feelings and experiences in marriage – she will get used to it and adapt.

Suddenly a silent, solitary gentleman, who was “evidently very anxious”, intervened in the conversation. He asked his companions what “true love means”, but no one was able to give a comprehensive answer. The gentleman said that true love was “only in novels and never in life”. They began to argue with him and then the gentleman confessed that he was the very Pozdnyshev who had murdered his wife. The incident was on everyone’s lips and they all kept quiet after hearing it. That night Pozdnyshev told his sad story to a fellow traveler.

Chapters 3-10

Pozdnyshev was a landowner, a university candidate, and had led a very promiscuous life before his marriage. He considered himself a perfectly moral man, and had no doubts that everything was going right. Pozdnyshev “gave his debauchery graciously, decently, for health,” and avoided women, who by some tricks could bind him to himself.

So Pozdnyshev lived until he was thirty and finally decided to “get married and make the most exalted, pure family life. One day he met the charming daughter of a ruined landowner. The girl was entirely in keeping with his idea of the ideal, and he rushed to propose to her.

Pozdnyshev, unlike most of his companions, “had the firm intention to hold on to monogamy after the wedding. He imagined himself to be a true angel, and this thought warmed him. Before the wedding, communication with the bride was very difficult – it ‘was a Sisyphean job’. With no sense of intimacy, the young people did not know what to talk about with each other, and the void between them was occupied by the pre-wedding bustle – “talk of flats, bedrooms, beds, bonnets, dressing gowns, linen, toilets.”

Chapters 11-18

“The lauded honeymoon began,” but it brought no joy to the newlyweds. A few days after the wedding Pozdnyshev “found his wife bored. He embraced her, but she only cried. She could not explain the reason for her bad mood, but her face eloquently “expressed the utmost coldness and hostility, hatred almost. Pozdnyshev was astonished. He had thought that love could not be associated with such terrible emotions. He soon realised with sadness that his wife’s hostile attitude was a permanent phenomenon, not temporary. It was then that Pozdnyshev began to guess “that marriage is not only not happiness, but something very hard.”

The couple quarrelled more and more often. In eight years of marriage they had five children, but this did not save the situation. On the contrary, the emergence of heirs further alienated the couple from each other. Pozdnyshev believed that “children are a torment, and nothing more,” and love for them is pure selfishness. The young wife had gone into the care of the children and had ceased to show any interest in her husband at all. But worst of all, the couple chose to use their children as a weapon against each other. They each had their own favourite and, despite the state of mind of the children, used them cruelly in their unmerciful games.

After a few years, all their communication was reduced to talking about the weather, children’s illnesses, dealing with domestic issues. The Pozdnyshevs were like “two well-wishers who hated each other, bound together by the same chain, poisoning each other’s lives and trying not to see it coming”.

After five children, Mrs. Pozdnysheva’s health declined, and doctors “told her not to give birth and taught her the remedy.” The young woman happily agreed, while her husband was indignant – “the last justification for pig life – children – had been taken away, and life had become even worse”. The doctor’s advice benefited the woman and she became noticeably more handsome, refreshed and attracted the attention of men on the outside. She no longer reacted so keenly to her children’s illnesses, spent more time on herself and her little whims, and even remembered her old hobby – playing the piano.

Chapters 19-28

Mrs Pozdnysheva seems to have been reborn for love, “but love with a husband shackled by both jealousy and all kinds of malice was no longer the case”. She soon got the chance to feel loved and wanted when Trukhachevsky – an attractive young man, a musician – appeared in their house. Pozdnyshev saw that his wife was interested in the violinist and jealousy set in.

At one musical evening, Pozdnysheva and Trukhachevsky played Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata. The music deeply affected Pozdnyshev, seeming an omen of something terrible.

Soon Pozdnyshev was off on business in the county, but he was troubled by thoughts of his wife and the musician. Unable to bear it, he returned home, where he found the lovers. At first he rushed to Trukhachevsky, but he quickly ran out of the house. Pozdnyshev rushed to catch up with him, but thought “it would be ridiculous to run after your wife’s lover in stockings,” and gave up the chase. Instead he grabbed a “crooked Damascus dagger” and in a fit of terrible jealousy stabbed his wife. But even before she died there was a “cold animal hatred” on her face. The dying woman’s last wish was that her own sister, not Pozdnyshev, bring up her children. It was only when the hero saw his wife lying in the coffin that he clearly understood what he had committed and “that this can never be rectified, anywhere, by anything.” Pozdnyshev spent eleven months behind bars awaiting trial, after which he was acquitted. However, he could never forgive himself for what he had done.