21.12.2022

“Tolstoy’s Childhood” ushers in an era of psychological prose in Russia: the penetration into the hero’s mind, the precise recording of his thoughts, the ruthlessness towards him are all characteristic marks of Tolstoy’s texts. This will allow him to show the psychology of a child, a teenager, a young man, a young landowner – with their arrogance and mistakes; the confusion of a participant in a senseless massacre and an outsider in a different cultural environment. “War and Peace” will be the ultimate expression of this Tolstoyian skill.

Childhood

Leo Tolstoy’s debut novel stuns his contemporaries not only with its theme (although present in literature, it has remained peripheral) but also with its approach: the semi-autobiographical Childhood and the subsequent Youth and adolescence are the most scrupulous and merciless observation of the psychology of a young man, a man in the making.

In Childhood it emerges that a child can have complex, contradictory feelings, that he can be selfish and tender at the same time, admire himself and scold himself, fall in love and grieve. The climax of Childhood is the death of the mother of the protagonist, Nikolenka Irteniev, or rather Nikolenka’s reaction to the event.

Boyhood

A direct continuation of “Childhood”: after the death of his mother, Nikolenka Irteniev and his brother move to Moscow to live with their grandmother, his love of childhood pranks is combined with introspection, and love for his older brother is mixed with envy.

Tolstoy describes the adolescent period as one of the most complicated in a person’s life. The figure of Irteniev does not fit into the speculative image of “man as he should be”: Tolstoy’s experiences are deeply individual, though they correlate with the experiences of almost everyone.

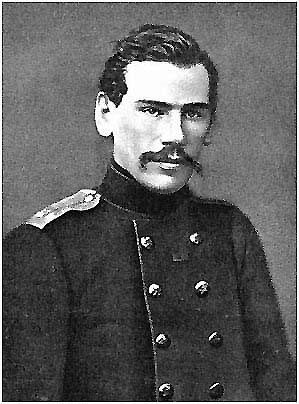

Tales of Sevastopol

Tolstoy takes part in the Crimean War as a well-known writer, and The Sebastopol Tales has the same stunning effect on readers as Childhood and adolescence did earlier.

Adhering to the methodology of the natural school (the first of the three stories is in the form of an essay, a kind of tour of the besieged city), Tolstoy concentrates not only on the heroism of the Russian troops, but also on the immediate war experiences, on the blood, horror and senselessness that blights healthy, beautiful and young men.

The Landlord’s Morning

Part of the unfinished novel The Novel of the Russian Landowner, this work is both a literary and life-building project of the young Tolstoy. The protagonist of the story, Prince Nekhludoff, is largely autobiographical, and his thoughts on the need to take care of the peasants and himself into all the affairs of his household are those of the writer himself. The tale presents various peasant types and ends quite idyllic, but its most valuable feature is the deep introspection, the character’s ability to look “inside himself,” which will become a major principle in Tolstoy’s major novels.

Youth

Nikolai Irteniev is sixteen years old, preparing to go to university. As before, his youthful narcissism alternates with periods of shame and even self-deprecation. He forms a friendship with Nekhludoff, a much older and smarter student, but is as yet unable to cope with temptation: in his merry revelry parties, Irteniev forgets all about his studies and fails his exams. The shock proves to be therapeutic: repenting, Irteniev prepares for a new period in his life. The fourth story of Nikolai Irteniev – “Youth” – remains unwritten, but the introspection developed in Tolstoy’s debut will become a vital device in Tolstoy’s later works – The Cossacks, War and Peace, Anna Karenina, and Death of Ivan Ilyich.

The Cossacks Partly an autobiographical novel by Tolstoy – about a few months of life in the Caucasus young cadet Dmitry Olenin: delighted by the Caucasian nature and the simplicity of the manners of the Terek Cossacks, he himself actively “pollutes”, trying to imitate his new friends and have an affair with the Cossack Maryana – but in the end he realises that he will always remain a stranger here. “The Cossacks” shows that the ideas that would be developed in Tolstoy’s later works occupied him already in the 1860s, and even at that rational time readers admired the psychologism and language of “The Cossacks,” still a far cry from Tolstoy’s late asceticism.