10.12.2022

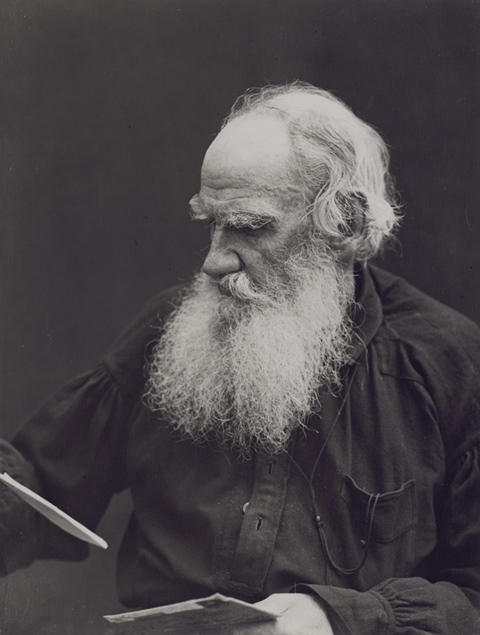

Ten days before his death, the 82-year-old writer literally ran away from home and hid from his wife. What happened to him before and after his escape, who was with him in those days – and how Russia reacted to the news of the genius’ death.

On 20 November 1910, one of Russia’s foremost writers, and arguably its most prolific, passed away. The elder’s eccentric nighttime escape from the Yasnaya Polyana estate became a detective story, which was actively covered by the press. And the whole country followed the last days of his life.

Spiritual upheaval and attempts to leave home

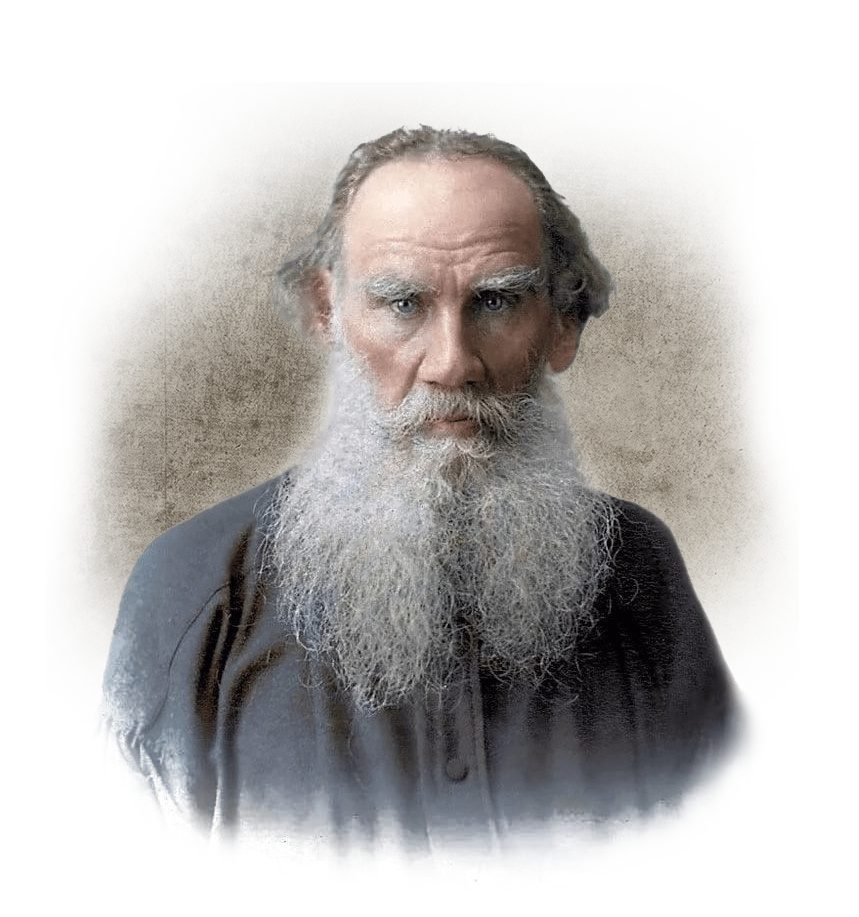

An exemplary family man, Leo Tolstoy for many years broadcast the importance of family values in his novels. Love, marriage, children – all this he considered the meaning of life along with constant spiritual self-improvement. But in the 1880s, already in his fifties, Tolstoy undergoes a major inner upheaval. He changes his attitude to religion, gets disappointed in church and in marriage as a sacred union of a man and a woman.

His attitude to private property also changes – Tolstoy tried to free himself from wealth, began to wear the legendary shirt, to work the land together with the peasants. He also decided to give up the copyright of his works – which caused a major scandal in the family. Tolstoy’s wife Sophia Andreevna was resolutely against this. After all, this meant that the family would be left without means and Tolstoy’s many children without an inheritance.

The upheaval that happened to Tolstoy was the first prerequisite for his flight. In the 1880s, the writer becomes obsessed with the idea of abandoning everything “corrupt”: the bargain lifestyle, its fame and money. He imagines the only way to end it is to leave home and lead an almost vagabond life, “merging with the people”.

Chertkov on Tolstoy’s shoulder

Tolstoy is greatly supported in these impulses by his admirer and personal assistant Vladimir Chertkov. He exerts a great influence on the writer, often and uninvited visits to Yasnaya Polyana, and even suggests that Tolstoy himself abandon his family, where his new philosophy is allegedly not understood.

Chertkov becomes an absolute irritant to Sofia Andreyevna. The atmosphere in the family heats up, there are constant conflicts between the spouses.

“Today he cried out loudly that his most passionate thought was to leave the family,” Sofia Andreevna writes in her diary in the summer of 1882. A week later another conflict arose, his wife accused Tolstoy of being irresponsible with the family money and he left home with one sack of clothes.

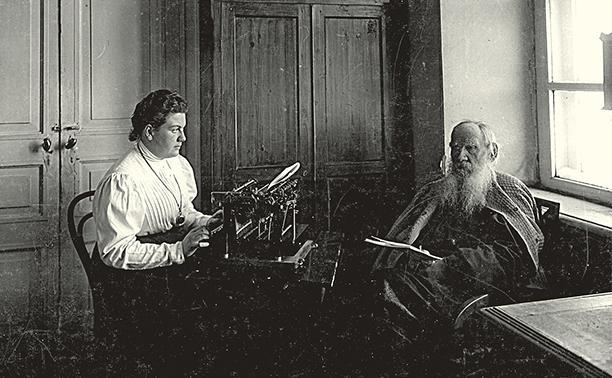

“Halfway to Tula he turned back because of the close birth of his wife. The next day their youngest daughter Alexandra was born,” writes Andrei Zorin in his biography The Life of Leo Tolstoy. The Experience of Reading.” Alexandra would become his personal secretary and devoted friend and assistant to her father. To her he eventually bequeathed all the rights to his works.

After 12 years, Tolstoy again wants to leave and even wrote a farewell letter to Sophia: “I could not leave you until now, too, thinking that I would deprive the children, while they were small, at least that little influence that I could have on them …”. However, he never gives the letter back, and stays at home. Then the contradictions between sinful thoughts and temptations, and the desire to lead a righteous life Tolstoy displays in the story “Father Sergius. It begins with a handsome officer breaking off his engagement, leaving his promising service and heading for a monastery. Apparently, Tolstoy himself dreams of such a fate.

Tolstoy declines the Nobel Prize when word gets out that he is going to be awarded it. He also goes to great lengths to prevent a major celebration of his own 80th birthday in 1908.

The desire to hide from the burden of fame was for him both a personal, social and artistic task – Tolstoy sought ways to reduce his own presence not only in the literary process but also in the text itself,” writes Zorin.

“Escape from Paradise”

On the night of 10 November 1910 (New Style), Tolstoy secretly fled, taking only a few belongings. He was accompanied by his personal physician, Makovitsky, who was awakened suddenly in the middle of the night and had no idea of the elder’s intentions. The next morning his daughter Alexandra handed his mother a letter in which Tolstoy informed her that he was leaving for good. “I am doing what old men of my age usually do. Leaving worldly life to live in solitude and in silence for the last days of their lives,” Tolstoy wrote.

Sophia Andreevna was in despair, she did not know where her 82-year-old husband, where he was going. Tolstoy was, perhaps, and strong old man, but he had fainting spells and even loss of memory, in addition, he had a heart condition – such an escape threatened his imminent death.

Tolstoy and his doctor boarded a train and decided to travel first to the nearest town, Tula. Pavel Basinsky, the author of the book about the last days of Tolstoy’s life “Escape from Paradise”, writes that the route, and more importantly, the final destination of the escape, was unknown to the fugitive himself: “Tolstoy had a clear idea of where and what he was fleeing from, but where he was going and where his final resting place would be, he not only did not know, but tried not to think about it.”

Soon the news of Tolstoy’s eccentric act became known to the local press, and Tula correspondents everywhere began to follow the writer; newspapers kept detailed chronicles of his actions and movements. “In Belev Lev Nikolayevich went out to the buffet and ate an egg.

By a complicated route, changing several trains, Tolstoy did indeed reach the monastery of Shamordino, where his sister lived, after which he decided to go south to Bulgaria – and returned to his railway voyage. On the way, the writer caught a cold, which resulted in a croupous pneumonia. Makovitsky’s doctor decided to take the sick man off the train at the nearest station.

One of the correspondents, who followed Tolstoy’s movements, telegraphed to Sophia Andreyevna: “Lev Nikolaevich is in Astapov at the station master. Temperature 40”.

Astapovo station – the last refuge

This small railway station in the Lipetsk region is now called “Lev Tolstoy”. In 1910, Astapovo was the focus of national attention. On November 13, a few days after he left home, the gravely ill Tolstoy was taken to the house of the station master – there was no better or more comfortable place to stay. The writer was almost unconscious and suffocating. Several doctors tried to save Tolstoy, but he asked not to bother him – and relied on God’s will.

Tolstoy’s situation got worried in the highest circles – even the officials in the capital convened meetings and the surrounding governors, the Ministry of the Interior and the railway authorities obliged the local police and station staff to telegraph as often as possible.

Journalists were the first to arrive at Astapovo, but gradually people of all walks of life and ranks began to arrive, as well as a huge number of the writer’s admirers. “One had the impression that during these seven days at the station, the fate of the empire was being decided, and that the entire globe was watching,” writes Basinsky.

His assistant Chertkov came to Tolstoy before anyone else. Tolstoy does not want to see his wife, categorically, and is even afraid that she will come, rambling at night: “To get away… To get away… To catch up…”.

And still Sofia Andreevna went to Astapovo – she knew about helplessness of her husband in everyday life and was very worried: “Who will give him some butter there! She wanted to see her husband, but, as Basinsky writes, “the collective decision of the doctors and all the children decided not to let her in and not to tell Tolstoy anything about her arrival.

Sophia Andreevna then decided to actively communicate with journalists. She was filmed for photos and newsreels and gave interviews, telling about forty-eight years of happy family life.

She was allowed to see Tolstoy a few hours before his death, when he was already unconscious. She “quietly walked up to him, kissed him on the forehead, knelt down and began to say to him, ‘Forgive me’ and something else I could not hear,” their son Sergei recalled. A large number of people came to Yasnaya Polyana to say goodbye. As Tolstoy himself bequeathed, the ceremony was not orthodox, but secular. And they buried him in the estate itself, without a cross or monument – just made an earthen mound, dotted with grass.