10.12.2022

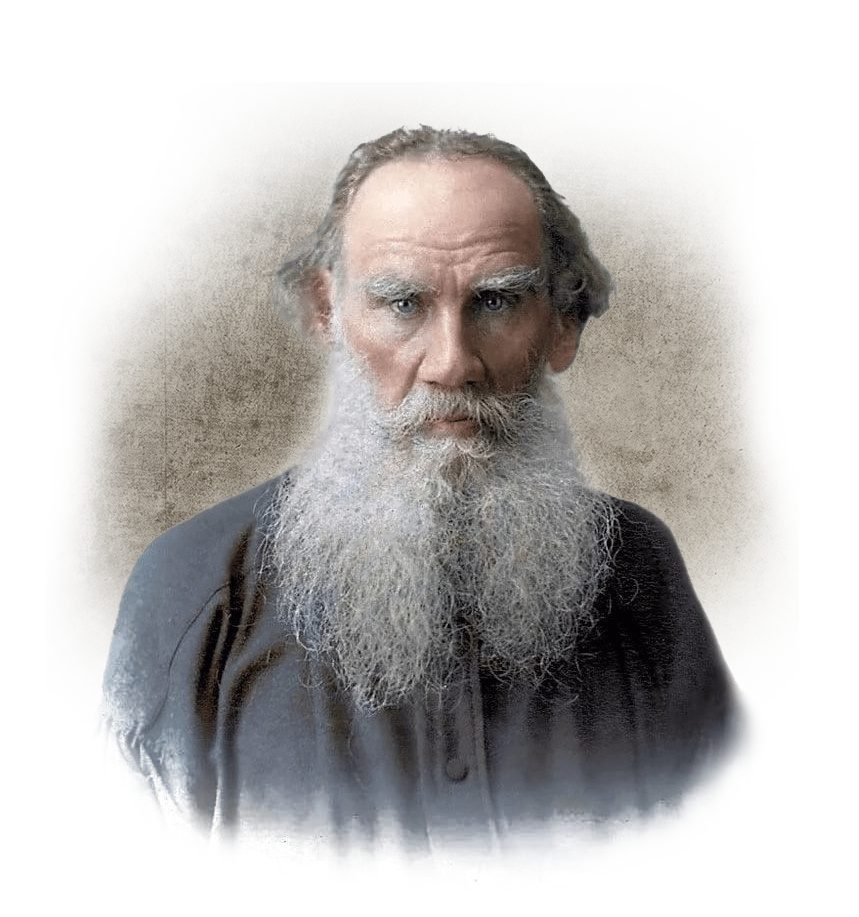

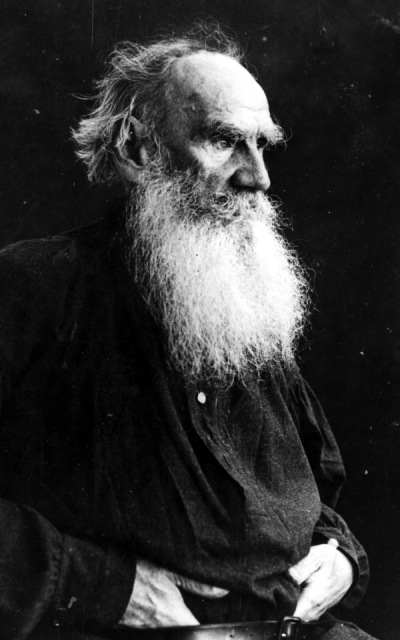

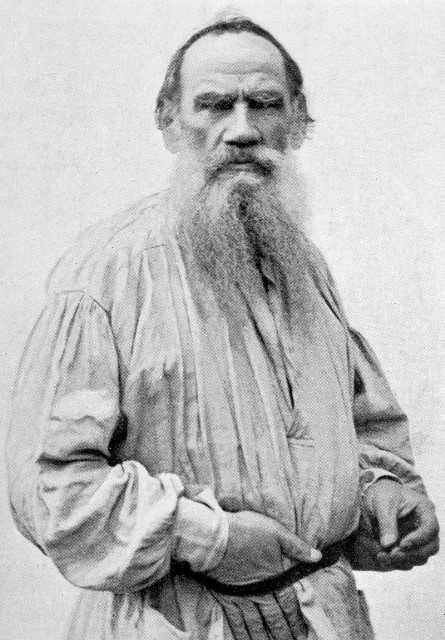

Leo Tolstoy was in his fifties when he began to experience an existential crisis, falling into a state of depression and melancholy. Despite the fact that he was one of the richest and most respected people in Russia, deep down he felts unhappy.

By this time Tolstoy had already shown his literary ability and had written two masterpieces – War and Peace and Anna Karenina. But he rejected his literary success and called his last novel “an abomination that no longer exists for me”. This novel, moreover, grated on the writer’s nerves in the process of creation. Sometimes Tolstoy would say, “I can’t stand it!”, “My God, if only someone had finished Anna Karenina for me!” or “My Anna bores me like a bitter radish!”

When he reached the worst stage of his life and began to experience suicidal thoughts, he wanted to give himself one last chance to see the light amidst the darkness of his existence. That’s when he translated his mental turmoil into an autobiographical memoir, Confessions. This book is the author’s struggle with his mental health and his attempt to find answers to his most important philosophical questions.

What triggered Tolstoy’s depression?

“The Confession” was written when Tolstoy was 51 years old. He described in detail how he felt when he was depressed:

“Life hated me, and some irresistible force made me seek deliverance from it by any means necessary. I’m afraid to admit it, but I thought about suicide, but I was afraid to do it. The force beckoning me away from life was a stronger, more complete and all-encompassing desire. It was a force similar to my desire for the afterlife, only it went in a different direction. I fought hard against life. The thought of suicide now came to me as naturally as the thought of improving life had come to me before.

All this happened to me at a time when I was surrounded on all sides by what is considered complete happiness: I was not yet fifty, I had a kind, loving and beloved wife, nice children and a large estate, which grew and expanded without any effort on my part”.

Tolstoy could not understand his feelings. In retrospect, he found that he had always strived for the ‘perfect life’ and competed with his peers:

“I tried to improve myself intellectually and studied everything I encountered in life. I tried to improve my will by making rules for myself which I tried to follow. I improved myself physically by doing all sorts of exercises to develop my strength and agility, and I cultivated endurance and patience by overcoming all kinds of difficulties”.

This path led him to the point where he felt that his life was futile and death was inevitable.

Tolstoy’s observation on how others may have coped with mental health problems

Tolstoy identified four approaches that people might have used to deal with the ‘futility of life’:

The first approach was ignorance and an inability to understand that life is meaningless. People in this category might not think about or think about the purpose of life.

The second approach is epicureanism. People in this category think that life is ephemeral and enjoy the time they have. But Tolstoy felt that this approach encompasses only those people who can afford an affluent lifestyle and leave behind the part of society that is necessary, cannot live the ‘good life’.

The third approach is ‘suicide’. People who realise meaninglessness ‘act accordingly and put an end to their lives’. Tolstoy admitted that he was too cowardly to do this.

And the fourth approach he found himself in was to live a life of futility, knowing that nothing would come of it.

What was Tolstoy’s solution? Tolstoy’s despair and anxiety increased when he realised that physical science and philosophy could not answer the most important question of his existence. Gradually he discovered that people who are poor, uneducated, enduring hardship and suffering, live the purest form of life. Although they spend most of their lives in toil, they are still ‘happy’ in their lives. On the contrary, Tolstoy found that people in his environment were rich but unhappy with their lives.

Tolstoy noticed that the more he understood the lives of the poor, the easier it became for him to live. Another enlightenment for him was helping the poor and suffering.

Final thoughts

Tolstoy abandoned his aristocratic lifestyle and lived the rest of his life preaching love, non-violence and helping the peasants. “I realised that if I wanted to understand life and its meaning, I must not live the life of a parasite, but must live a real life, accepting the meaning given to life by real humanity, and dissolving in that life.”